THE tome titled Fulvia is Scotland-based historian and archaeologist Dr Jane Draycott’s reverse-engineering of the life of an aristocratic woman identified by the same name, reported to had broken all the rules in ancient Rome during her lifetime in the dying days of the Roman Republic sometime around the year 80 BCE (Before the Common Era).

The sum total of an unusual life dissected by the Roman history scholar and lecturer in Ancient History at the University of Glasgow – with Fulvia, Draycott expressly sought, through literary, documentary and archaeological evidence, to reconstruct how a woman who, although neither a goddess nor an empress, was able to amass her own degree of political and military power in a society which was notoriously patriarchal and chauvinistic.

Draycott’s reconstruction of Fulvia’s accurate portrait wasn’t made any easier due to the unreliability and inconsistencies of the authors of her epoch, whose portrayals of her were hostile and alternatively bothered on exaggerated falsehoods intended to provoke varying reactions. It was against such a background that Draycott embarked on a quest to glean a semblance of the truth regarding her subject matter by casting a critical eye over the ancient evidence, reading between the lines and proposing an alternative interpretation to the then and now existing misogynistic perspectives about Fulvia.

A woman who remains known by a single name, and whose precise dates of birth and death are unknown – Fulvia was born into wealth, privilege and prestige. In an ancient Rome trending with so-called advantageous marriages (arrangements among families primarily focused on consolidating wealth, status and political power rather than love), being the last scion of two wealthy families and an heiress twice over, meant Fulvia wielded much more influence in all three of her marriages to men (who included Julius Caesar’s general, Mark Antony) who wielded political and military power.

In what is referred to as the most famous single episode of her storied career, Fulvia went to war in Italy with her husband, Mark Antony’s rival, viz, Octavian – in order to protect his interests while he was away in Egypt. During what is today known as the Perusine War, in the winter of 41–40 BCE, Fulvia rallied support for her spouse by recruiting legions who occupied Rome in an unprecedented deed of valour associated with a woman – after Octavian had decided to take advantage of Antony’s absence by marginalizing him through the confiscation of landowners’ land and reallocating it for the foundation of colonies of Roman veterans in order to curry favour with them.

Described by historians as a brutal civil war, a sword-draped Fulvia is limned as having been involved in strategizing, issuing orders and handing out military watchwords to soldiers on duty during a conflict in which psychological warfare was additionally waged in the form of lead sling bullets bearing insulting inscriptions intended at all participants in the battle.

Although the conflict resulted in victory for Octavian (a member of the Second Triumvirate – a dictatorial magistracy composed of himself, Lepidus and Mark Antony, formed during the final years of the Roman Republic) – it wasn’t the first instance Fulvia (the de facto third member of the triumvirate around 41 BCE) had seized the cudgels for a husband of hers.

After her first husband Clodius had been brutally murdered, she leveraged her political power to avenge his death by manipulating public perception when she brought his corpse to the streets of Rome so that citizens would behold his wounds and be induced to ire towards Milo, the nemesis who had ordered his assassination.

Later, instead of according her husband the conventional funeral comprising of a cremation, Fulvia had his corpse deposited to the Senate House where, on a makeshift funerary pyre consisting of benches, tables and public records, it was set afire – instead of outside the city’s boundary – along with the house!

Thereafter, her testimony at a subsequent trial resulted in Milo’s conviction and exile from Rome.

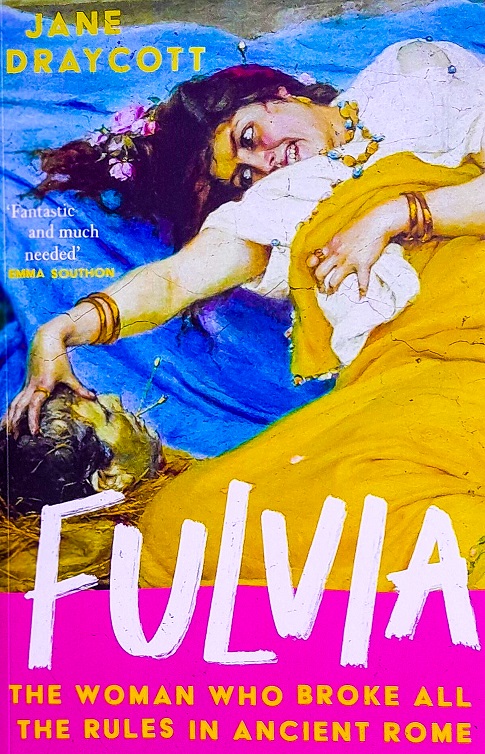

Cicero, the foremost orator of the era – and both herself and Mark Antony’s detractor – would accuse her of being a curse upon her husbands, labelling her ‘a woman as cruel as she is greedy’. Such invective precipitated the infamous incident in which she’s reported to had spat on Cicero’s decapitated head and punctured his tongue with her hairpin upon it being presented to her after Mark Antony had ordered his assassination around December 43 BCE. (A painting appearing on the tome’s cover by the 19th century Russian artist Pavel Svedomsky limns such a grotesque scene.)

Depending which version is credible, contradictory portraits of Fulvia abound.

The Greek philosopher and Mark Antony’s biographer, Plutarch claimed that she was ‘a woman who took no thought for spinning or housekeeping’, but who ‘wished to rule a ruler and command a commander’. Conversely, in what can be interpreted as a compliment, the self-same Plutarch ventured insofar as to claim that ‘Cleopatra (the Queen of Ptolemaic Egypt who rendered her a cuckquean due to her affair with Mark Antony) was indebted to Fulvia for teaching Antony to endure a woman’s sway, since she took him over quiet tamed, and schooled at the outset to obey women’.

Further described by another historian as having ‘nothing of the woman in her except her sex’, Draycott’s account delves into the life of a woman who revolted against being rendered a mere helpmeet to her family, and assigned the traditional woman’s chore of spinning and weaving – who, instead differentiated herself from her peers through her actions and bravado.

In the end, Fulvia’s actions in Italy – despite their having been in ensuring the safety of her husband (i.e., Mark Antony), children and property – were criticized by Antony, whose anger exacerbated her health, and combined with his abandoning her on her deathbed faraway from Rome, precipitated her eventual demise.

So why then, questions Draycott, is Fulvia treated so differently?

A trade paperback, Fulvia is published by Atlantic Books and distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R450.