“AIN’T nobody ever heard of Beyoncé, so this child will be original,” an expectant Tina Knowles responded to her dad Lumis’ scoff “that this baby is gonna be real mad at you for naming them with a last name” whilst they were discussing the name she intended bestowing unto her unborn child – just a few weeks from delivering, back in August of 1981, in Houston, Texas.

Knowles purposed to retain her maiden surname – which is tied to her rich Louisiana Creole lineage reflecting a mix of African, French, Native American, and Spanish ancestry – because she didn’t want for it to become extinct.

For starters, Knowles’ maiden surname, Beyoncé, wasn’t even identical to her father’s, which was Buyince – as well as those of some of her four siblings, which variated from Beyincé to Beyoncé. Even her paternal grandparents’ surname, Boyancé, was an extension of the variation – a consequence of the United States’ segregationist bureaucracy, for which details such misrepresentation of black Americans’ identities it either considered trivial or unworthy of fussing over.

And that her dad could even be discussing names with her belied the reality that he didn’t know how to read or write. ‘Twas a discovery which shocked the then young Knowles – who shared a daddy’s-girl kinship with him – whilst growing up under the love and protection of the kind former longshoreman, in Galveston, Texas.

Further regarding names, in 1964, Knowles herself had herself renamed Tina – a substitution of Celestine – whilst registering for fifth grade schooling.

The lastborn in her family, who went by the moniker “Badass Tenie-B” – imposed upon her on account of her moving quicker than she could think – she had detested her given name, and through her own terms, was able to assume a new identity as: Tina Beyoncé.

‘Twas unbeknownst to her conformist mother, Agnes, who, back whilst Knowles was still a pre-school juvenile, had maintained: “You can’t change your name.” Agnes it had been too who had informed the opinionated girl child to “be happy that you’re getting a birth certificate”, when she queried the matriarch why she couldn’t make the bureaucrats rectify their family surname?

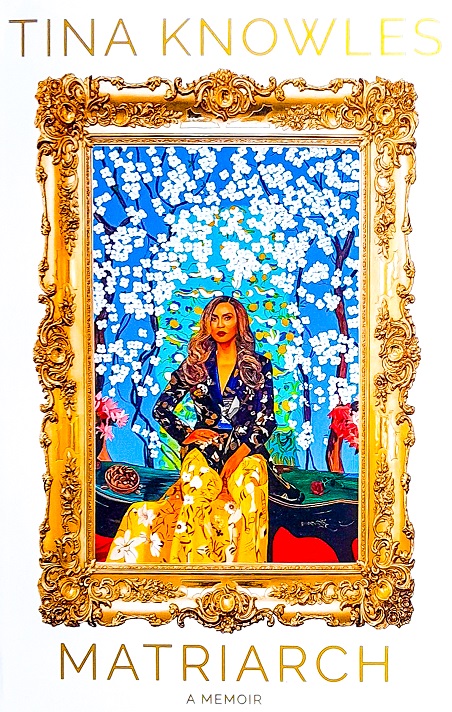

The afore-mentioned biographical background is contained in the early chapters of Knowles’ memoir, Matriarch.

In it, Knowles takes readers through a childhood experienced in the 1950s whilst growing up under the nurturing of her loving parents – the equivalent of folk African American activist-author Clifton Taulbert referred to as, “original Colored folks”, in his evocative memoir, When We Were Colored.

There was the period of unease she endured at Holy Rosary Catholic School whilst aged about six, mainly at the mercy of an ill-tempered nun who made her unwelcome by informing her she didn’t belong at the school, just because her parents were indentured servants (her dad toiled as a chauffeur at the nuns’ beck and call) to Holy Rosary, bartering work in exchange for tuition for her and her siblings – an arrangement not lost on her malicious teacher, who affronted: “You don’t belong here.”

Definitive experiences in Knowles life involve the “best friends for life” kinship she shared with John “Johnny” Rittenhouse who, although four years her senior, was her nephew.

Together they created countless memories, inter alia: from her dutifully shielding him from the taunts of the “hardass little town” of Galveston’s residents – owing to him being gay; him becoming the nucleus of the Knowles’ family by housekeeping and forming a unique bond with her daughters, Beyoncé and Solange; and onto to the moment in July 29, 1998 when Johnny drew his last breath aged 48, allegedly from AIDS-related dementia – with Knowles reminding one and all that he was her best friend.

Knowles also takes the reader through the gumbo dish of her Louisiana Creole heritage her mom taught her how to cook, navigating the stages of the recipe: from cutting the celery down to the millimeter; coring the bell pepper and onions; adding chicken and crab into a giant pot of seasoned water; making the roux by periodically stirring it to a colour of dark fudge; frying the okra in a skillet; adding the sausages and thereafter patiently babysitting the pot for hours.

The mother of music megastar Beyoncé, Knowles also mentions her own stint in music, as a singer in a group composed – like her daughter’s – of a trio of females named the Veltones.

Although the girl group did well on the talent show circuit for a while, it eventually folded sans even clinching a record deal it had aspired to. She would thereafter venture out for some period as a vocalist accompanying a band which performed for tourists at a local club.

With a singing career not working out, Knowles would persevere on to branch into a cosmetology career by launching her multimillion-dollar brand, Headliners Hair Salon for the Professional Woman, in Houston in October 1986.

By that moment, she had already had a foretaste of the industry when she momentarily worked for a cosmetic brand in Los Angeles in 1973 where on one occasion Tina Turner came over to her kiosk to enquire about lip gloss.

Other segments in the tome make mention of how Knowles met and married Mathew – the father of her two daughters – and broke up and reconciled with him.

She proffers details on becoming the mother to one of the universally-renowned public figures of all time – including how she and her husband came up with the name, Destiny’s Child and helped guide the girl group to global acclaim.

In the prelude, Knowles surmises: We all have this power to be matriarchs, to be women of the sacred practice of nurturing, guiding, protecting – foreseeing and remembering. The matriarch’s wisdom is ancient, for she is filled with the most enduring, ferocious love.

This is the recollection of a grandmother and a Matriarch to many, whose mom would always say: “Pretty is as pretty does.”

A trade paperback, Matriarch is published by Little Brown and distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R470.