ON the Sunday of October 15, 1916, a too astonishing to be real scene unfolded below a ridge in the Elsburg valley located on Johannesburg’s East Rand, involving separate contingents of thousands of African men dressed in moochis made of animal skins, and armed with assegais and oxhide shields – who closed in on an ox-wagon laager, behind which massed hooded white men armed with old-time muzzle-loader rifles, waiting to open fire on their advance.

As the impi approached, several white men started firing their rifles at them and colleagues on horseback stormed past them whilst shooting at the warriors – telling some of them to leave their bodies scorched and bloodied. Angered by the whites’ actions, the Africans retaliated by rushing at the wagons and pulling horsemen from their saddles.

Amidst the melee, an instruction in Dutch was bellowed to: “Shoot the devils!” As mayhem reigned, some of the warriors penetrated the laager, only to find themselves blocked by a ten feet deep dam.

And when a separate impi charged down from a koppie towards the laager with the intention “to kill every man in the laager”, a group of policemen managed to intercept their incursion. The carnage left one man dead, 135 others injured – most of them African – with some ending up hospitalized.

Except the dead man, none of the thousands of people involved in the ‘carnage’ were meant to get injured or lose their lives since the incident deviated from a movie script. In the aftermath of what had occurred, an Inspector Trew was informed that there had been a plot to sabotage the day’s filming, involving the whites – who were extras cast in the role of Voortrekkers – deliberately provoking the Africans just to cause trouble.

Furthermore, evidence gathered indicated that there was an infiltration of unauthorized persons who obtained rifles – one of which, along with some of the blank ammunition, would be subjected to an inquest presumably owing to suspicion of its having been tinkered with.

The ‘scene gone awry’ had been a re-enactment of the historic Blood River battle between Afrikaners and Zulus – and incidentally, the fortuitous bad blood expressed by the actors on the set educed what spilled over between the forebears of the ‘antagonists’ back in 1838. Despite passing the approval of the South African prime minister at the time, viz, Louis Botha – the sabotage was alleged to have been instigated by elements who formed part of a sector of the public opposed to the movie titled, De Voortrekkers.

The scene had been African Film Production’s biggest and most important and its filibustering put the movie on the brink of collapse.

The dam in front of which the warriors had found themselves entrapped had been filled with two million gallons of water bought from the Rand Water Board and filled a stream which represented the river along whose bank the historical battle was to be filmed. Of an ambitious scale, the production had deployed personnel ranging from a Pretoria-based historian named Gustav Preller, scenario writers, researchers, artists, builders, costume makers, et cetera.

Additionally, dozens of old ox-wagons had been recreated, old-time muzzle-loaders scoured, and thousands of assegais and knobkieries made, as well as outfits for some 6 000 people (who included white extras who’d play the role of the Voortrekkers and migrant labourers recruited from one of the East Rand Proprietary Mines’ mines, who’d play the Zulu warriors’ role, respectively) stitched together by a costume department.

An affinity with the Afrikaner Boers had led the production company’s American tycoon proprietor, viz Isidore William Schlesinger, a.k.a. IW, to decide to make the retelling of the most sacred event in Afrikaner history – an epic about the Great Trek and Blood River – his first movie spectacle!

And his intrigue with the Zulu nation had motivated him to have a replica of a Zulu village – a kraal of almost six dozen structures composed of 70 beehive huts – constructed on a Killarney studio named City of Film, to accommodate “a head boy of the police” discovered at a Stanger police station named Tom Zulu, along with his wives, children and followers numbering several hundred people, whilst they awaited to be casted.

Although a stickler for verisimilitude, which had him insisting on filming on locations, some of IW’s films were produced at his 20 000 square feet City of Film comprising of offices for himself, his directors, managers, scenario editors and writers; a place for the creation of posters; a library and reading room; kitchen and dining room and mess hall; and ateliers for carpenters and costume makers.

In addition, it had an open-air stage and water features, garages for vehicles to be utilized in movies, and a place for the training of animals, et cetera.

Complementing the infrastructure were film crews IW recruited who comprised, among diverse reputable hands, the intrepid Englishman cameraman Joseph Albrecht and experienced American directors Lorimer Johnston and Harold Shaw – in addition to actors who’d been part of touring theatrical groups from England such as Mabel May, a British film star he’d marry, as well as a Dane named Holger Petersen whose good looks made him ideal for a hero role.

Others included technicians, a San Franciscan who became a studio manager and a circus master who’d train men and women to perform stunts, ride horses and steer chariots – among a motley crew necessary for the realization of a film production.

Furthermore, IW was one of the first filmmakers to cast African actors in leading roles and an employer of extras in huge numbers (25 000 by some account).

(An actor named Archibald Zonzo Goba who was cast in the first South African drama released by African Films, about a faithful Zulu farm hand who frustrates the schemes of half-caste stock thieves, titled A Zulu’s Devotion – would become the most important African actor at IW’s studio.)

Pending the 1920s when silent films were prevalent, IW was one of the first to make a ‘talkie’ film – and within several years stretching from 1916 to 1922, his movie company would produce some of the gigantic and expensive feature films the world had ever viewed – which included the first versions of some now famous remade movies, i.e., King Solomon’s Mines and The Blue Lagoon.

Afore venturing into movies, IW had acquired most of the theatres located across South Africa’s major cities – prominent of which was “the handsomest theatre on the subcontinent”, viz, ‘The Empire’, located in the Johannesburg CBD – under the grouping African Theatres, and subsequently had his movies shown in them, with him offering their erstwhile owners to manage them.

A globalist, he established a London-based entertainment group, the International Variety & Theatre Agency through which he disseminated both his theatres and movies operations. Through the parallel South African-based division, African Films movie company – he was able to produce huge spectacles comprising epic story lines!

Described as “a man with his soul aflame” and able to “sell hot potatoes in Hell”, IW was a Hungarian Jew from the Lower East Side of New York City, who’d left his home aged 24 in 1894 with almost nothing except a fob to sell insurance around southern Africa, through which he would invest in various business such as real estate (he established suburbs such as Parkhurst and Orange Grove), agriculture (which included “the biggest orange estate in the world”, at Zebediela) et cetera – which contributed to the fortune he would accrue.

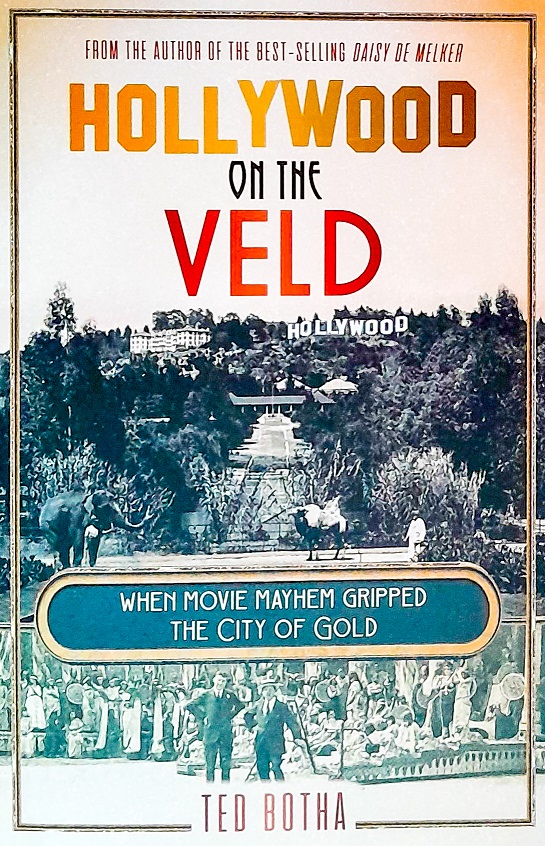

In 1913, three years prior to the shooting of De Voortrekkers, IW had had a crazy idea of producing movies in the ‘City of Gold’ – which would rival any made at a Hollywood which at the time was a piece of farmland, still in its infancy. He’d realize such a feat, replete with the studio constructed on 26 acres of rocky koppies, broad slopes and wooded streams – he converted into a ‘Hollywood on the Veld.’

Author, Ted Botha – a journalist who has worked for Reuters in New York and has written numerous books, including Daisy de Melker – described the experience of unearthing IW’s story as having been a long, frustrating and fascinating one whose research took him to libraries and archives at locations such as Johannesburg, New York, Cape Town, London and Cambridge.

His read is a never-told before story of how ‘Hollywood on the Veld’ emanated.

A trade paperback, Hollywood On the Veld is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R320.