“THE heart of the violence has been ripped out,” announced Minister of Law and Order, Louis le Grange’s spokesperson Leon Mellett, on July 24, 1985 after police had detained 665 people during the State of Emergency under PW Botha’s repressive regime.

Among those rounded up was the 23-year-old son of a preacher and leader of the Alexandra Youth Congress who would be hauled off to “Sun City” (Johannesburg Prison) where he’d be incarcerated, sans trial, for four years until he was released just a year before the announcement of the unbanning of anti-apartheid movements on February 2, 1990.

The bishop’s child, Paul Mashatile had initially earned his “Struggle” credentials amid the mayhem of teargas and police Casspirs rumbling down the London Road of his neighbourhood Alexandra – whilst, along with homeboys such as Nkenke Kekana, Obed Bapela, Mike Maile, et al, he pursued the realization of a democratic South Africa through activism in the form of leading civil disobedience against apartheid injustices.

He catapulted from, inter alia, instigating consumer, rent and bus boycotts – to becoming co-opted to the ANC’s PWV region in preparation of the looming political transition which culminated in the advent of democracy in 1994.

He would, from 2007, become the ANC’s Gauteng chairman for more than a decade and rise to the party’s deputy presidency in 2022.

In his role as the party’s Gauteng chairman, he displayed heft in the e-toll debacle when he opposed national government’s imposition of the system on the province’s motorists. That was just one of the instances Mashatile had defied then president Jacob Zuma’s administration. He once humiliated Zuma’s choice, Nomvula Mokonyane, by forcing her – as Gauteng’s then premier – to appoint into her cabinet, comrades loyal unto him.

The two apparatchiks just wouldn’t be spotted drinking tea together.

Zuma once responded: “Ngizwe ngani ukuthi lomuntu yisela” (I learnt from you that this person is a thief) – upon Mashatile’s name being put to him for consideration as a candidate for the Gauteng premiership.

One of the junctures Mashatile expressed his efficiency was as the chairperson of parliament’s Standing Committee on Appropriations – an oversight body permitted to control the national budget. Pending a 17-month tenure, he’d oversee some 73 meeting which, inter alia, dealt with: the adoption of a plethora of bills.

Those who know him variably describe him as a master tactician, ‘efficient and decisive’ and an ‘exceptionally capable politician’; an own man who, with time, will become president of South Africa.

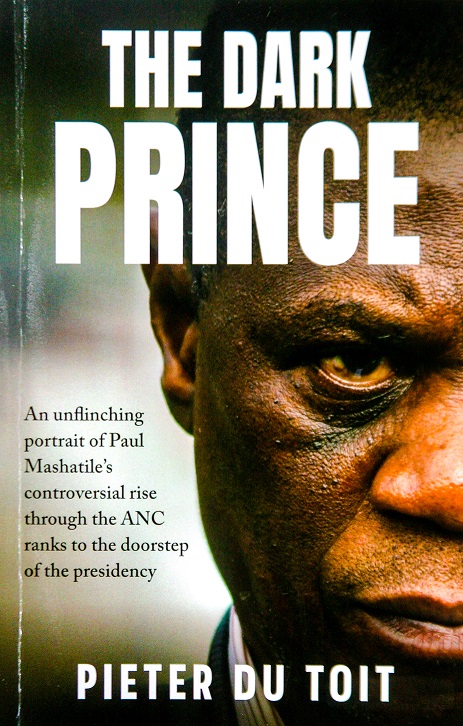

The afore-mentioned details are contained in Pieter du Toit’s new tome, The Dark Prince – in which the bestselling author of tomes such as the Stellenbosch Mafia and the ANC Billionaires also extensively touches on Mashatile’s links with the so-called Alexandra Mafia (alleged to chiefly comprise of Keith Khoza, Nkenke Kekana, Bridgman Sithole and Mike Maile) and credibly mentions instances in which the ‘circle’ benefitted from government resources.

The Gauteng Shared Service Centre was rumoured to be at the centre of the group’s fortunes, and provincial entities such as the Gauteng Economic Development Agency, the Gauteng Film Commission and Blue IQ were also headed by associates and allies – wrote du Toit.

The author further notes that based on investigative journalists reports, Mashatile is at the centre of concentric circles of networks which overlap and intersect – with business, personal and political networks often converging, sometimes diverging.

On a personal front, du Toit writes of a deputy president whose marriage to his present spouse in 2023 set off a firestorm among his various love interests – with one, Gugu Nkosi (who claims to have been romantically involved with him for eight years), allegedly prompting his relocation to another neighbourhood after she had confronted him at his previous house.

Among Mashatile’s pick of girlfriends, the read portrays Nkosi as a high-maintenance consort whose every whim the politician and his businessmen friends felt obliged to meet.

The businessmen – beneficiaries of government tenders – are said to have splurged millions towards her upkeep.

Concerningly, for a deputy president bidding to become South Africa’s president, Mashatile is portrayed as having a flippant approach to questionable issues which would be an impediment on his suitability as a future head of state.

These include casually dismissing of his association with dodgy characters such as the fraud-implicated businessman Edwin Sodi. The author questions how a politician on a public servant salary can afford to simultaneously reside in a mansion worth almost R40 million in Midrand and another worth R28 million, in Cape Town.

Don Pablo’s (as Mashatile’s circle refers to him) tastes extended to holding court, perched on a high-backed chair at the R300 000 per annum members-only SA Wine Bank in Melrose Arch surrounded by his inner circle, whilst they dined on five-star cuisine and expensive rare wines from across the world.

‘The Don’ is not averse to good food and fine wine running into the tens of thousands of rands – wrote du Toit.

Family-related question marks also punctuate his radar: with enquiries around the origins of the millions his son-in-law purchased the afore-mentioned mansions with; the revelation regarding the awarding of the lucrative national lottery licence to a consortium Mashatile’s sister-in-law is a shareholder in; and how companies linked to his children were able to accrue millions from tenders awarded by a Gauteng governmental agency.

Crucially and critically, du Toit also enquires regarding what Mashatile stands for, considering his designs to succeed President Cyril Ramaphosa at the Union Buildings after the next general elections.

Having been launched on a ‘Mashatile iThemba Lethu’ (Mashatile: our hope) ticket by those who have earmarked him as the ANC and the country’s next president – du Toit’s narrative scrutinizes Mashatile’s suitability to the country’s highest office.

Ultimately, du Toit marvels at Mashatile’s ability to had survived more than 35 years in formal politics, pending which he weathered storms of setbacks and bid his time during periods of political exile – to later utilize his incumbency to bid for the ANC presidency in 2027.

Could the master tactician from the ‘Dark City’ (Alexandra) described by friends as just loving people be the dark horse which, in a field in which has now been added billionaire Patrice Motsepe’s name, will pip opponents to the post – the Dark Prince hints!

A trade paperback, The Dark Prince is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R340.