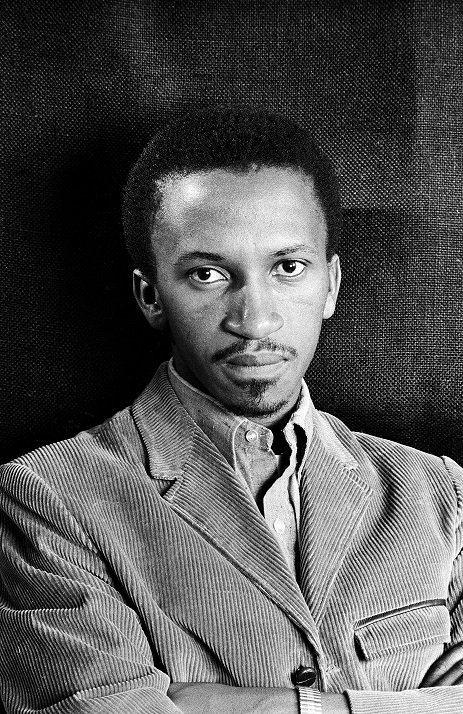

26-YEAR-old photographer Ernest Cole’s hasty flight from apartheid South Africa on May 9, 1966, never more to return, could read like a spy thriller in the genre of Cold War noir carrying a John le Carré-esque title along the lines of: The Photographer Who Came in from the Cold – the late journalist and Scorpions crack investigator, Ivor Powell, once partly wisecracked.

“The flight from servitude, even from an identity, involves spycraft too,” additionally ventured American cultural critic, Lauren Michele Jackson in a 2022 New Yorker article in which she discussed the Black American-born French singer and dancer Josephine Baker’s “turn at espionage” in the 1930s.

From the moment he fled South Africa, Cole – the greatest of the anti-apartheid photographers – was virtually stateless (the apartheid regime annulled his passport – rendering him to live the next 24 years in exile in the U.S. and Europe until his death in 1990). He was almost completely erased from the history of the South African struggle but for an eclectic network of characters whose connivance assisted in the preservation of his work.

These included the American, Joseph Lelyveld, a New York Times correspondent (who’d be notified that he’d be expelled from South Africa, upon the government’s knowledge of his ties to the lensman) who smuggled some of his prints and films out of the country – as well as the then United States Information Services Cultural Affairs Officer in Johannesburg, Argus Tresidder, who concealed some of Cole’s negatives in the USIS reading room and would later smuggle several boxes of prints to the US embassy in Nairobi.

The cast of characters also comprised a mysterious Yugoslav masquerading as a ‘journalist’ – but who’d eventually be exposed as a police spy – the USIS deepthroat referred to as Cole’s “your friend”, who often lingered around Cole’s friend and fellow photographer, Struan Robertson’s darkroom. By 1963, when he was briefly employed by Ruth First – the anti-apartheid activist and editor of the communist newspaper, New Age – Cole had become a “Person of Interest” to the Security Police, who kept him under surveillance.

It didn’t help his cause that he had in his possession a documentary he’d clandestinely been photographing which would constitute the tome, House of Bondage – the hard-hitting indictment on apartheid he would reveal eighteen months later after absconding.

Factoring in his personal safety and considering that his reclassification from African to Coloured (he altered his surname from Kole to Cole) made the securocrats to have him in their sights – he was left with no option but to take flight!

The plot would only get murkier once he’d reached the ‘safety’ of exile, with rumours – of his having friends within the American intelligence services and the CIA furthermore reported to have utilized the Ford Foundation (which funded his project which would culminate in this tome) as a conduit for the development of U.S. cultural nationalism interests in Africa ostensibly, among varying strategies it employed, through support of an anti-apartheid creative such as himself – no sooner circulating around him.

(A New York Times report of 1978 would reveal that “the CIA recruited U.S. blacks in the late 1960s and early 1970s to spy on members of the Black Panther party in both the United States and Africa.”)

Questions were also raised regarding the scale of funding for Cole’s project, academically named, A Study of the Negro Family in the Rural South and A Study of the Negro Family in the Urban Ghetto, which culminated in this tome under review.

By late 60s and early 70s estimations, it was deemed a dramatic amount ($10 000 annually in 1967 – the equivalent of $90 000 in 2023) – enough to encourage speculation that his was a grant intended beyond its stipulated purpose.

His relocating to Stockholm – where Tresidder had incidentally been reassigned to after Johannesburg – furthermore raised speculation that he’d been enticed by his old acquaintances in the American diplomatic service, into the chaos (droves of American deserters and draft-resisters opposed to the Vietnam War had converged on the metropolis) unfolding there in the late 1960s.

Against a backdrop of so-called spy photographers (for instance, Ernest C. Withers, the African-American photojournalist who documented Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement, would become exposed as a paid informant for the FBI) Cole could had arrived in the Swedish capital for an entirely different errand than seeking residence as a stateless person.

It’s hinted that he may have been tasked with photographing Black Panthers hiding out in Sweden. A movement Cole had enthusiastically documented (he photographed, Stokely Carmichael – one of its leaders who’d later marry Miriam Makeba – at a “Free Huey” rally in Los Angeles in February 1968) – the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover had demonized it as “the greatest threat to the internal security of the nation” and the CIA’s domestic spying program targeted it by sending Black agents in its employ to rallies and other public events so as to suss out its rank and file.

Eventually in late 1971, having been wont to a jet-set lifestyle the grant had accorded him all along, Cole’s funding was suddenly discontinued – speculated to be a consequence of having been stood down by shady figures working through the Ford Foundation.

In the mid-1970s, he appeared to had been bogged down in the Slough of Despond, with him apparently experiencing a massive crisis of faith in photography.

In the end, a combination of factors had taken their toll upon the Eersterus-born native once assimilated into the bohemian culture of a Mamelodi where the Malombo drummer Julian Bahula was a childhood friend – who succumbed from pancreatic cancer aged 49 in New York on the very February the last of South Africa’s apartheid leaders announced the demise of the repressive system which had rendered him a “banned person” from his country.

These chilling aspects to Cole’s biography are revealed by James Sanders – an American journalist and scholar specializing in South African history and politics – who has concentrated his research on Cole’s life.

The imagery featured in this tome were recorded between late 1967 and early 1972 and were neither dated nor captioned by Cole.

They were selected from over forty thousand negatives of North American films (part of a total of 60 000 which have been missing for more than forty years) found inside a safe at the Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken in Stockholm, and handed over to Leslie Matlaisane of the Ernest Cole Family Trust in 2017.

The meticulous monograph includes images of fellow photographer, Alf Kumalo, who is limned donning a fedora with a camera dangling from his abdomen whilst standing on a bustling Manhattan street corner during a visit to Cole in 1971.

Others, inscribed with contrariwise statements, limn a man on a Memphis sidewalk carrying a placard onto which the words, “Didn’t Come from Africa. How Can I Go Back?” – with another, displayed on a board placed on a convertible automobile passing along a Pan-Africanist parade in New York reading: “Don’t Riot Get Wise Go to Africa.”

The irony wasn’t lost on Cole regarding the America he abruptly sought refuge at, for – apart from the ignominy of it not granting him citizenship despite the lengthy period he resided there – he became surprised to discover bitter White racism, which disabused him of the impression that being Coloured, unlike in South Africa, didn’t matter there.

Whilst photographing in the seedy American South of the Klu Klux Klan for instance, he noted that he wasn’t “afraid of being lynched, but afraid of being shot.”

Regarding a soul ruefully at the mercy of politics of racialism and the Cold War, James Baker, the first African-American diplomat assigned to South Africa in the 1970s, claimed that Cole alienated Black South African refugees by insisting that he was Coloured not Black – when he arrived in New York.

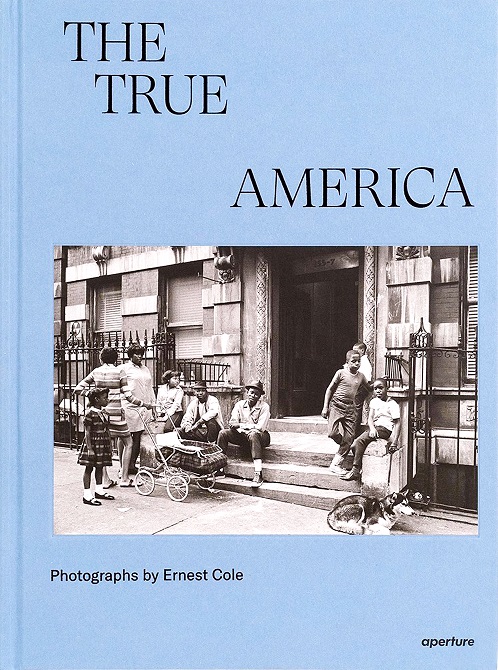

The True America is the first publication of photographs taken by Ernest Cole in the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The tome’s preface was written by Raoul Peck, the Haitian filmmaker who produced Ernest Cole: Lost and Found – the 2024 documentary film on Cole which won the L’Oeil d’or prize for documentaries at the Cannes Film Festival, as well as the Best Documentary award at the 2025 Joburg Film Festival.

A hardback, The True America is published by Aperture and distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R1 600.