“TELL De Klerk to speak to the ‘old man.’”

Erstwhile head of South Africa’s National Intelligence Service, Niel Barnard advised the then chief negotiator for the National Party government during the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) negotiations to end apartheid, viz, Roelf Meyer – after he had just revealed unto him the shocking news that the General Secretary of the South African Communist Party, Chris Hani, had just been assassinated!

‘Twas around lunchtime of Easter Saturday on April 10, 1993 and the unexpected news had triggered a frantic reaction from F.W. de Klerk, the president of South Africa, who – vacationing for the Easter break on his family’s farm at Steynsburg in the Karoo – now found himself scurrying around rallying his lieutenants so as to come up with an appropriate reaction to a sudden crisis which could scupper three years multi-party talks aimed at shifting South Africa away from decades of pariahdom and usher it into a democratic epoch.

Such a development throwing the CODESA deliberations – which had resumed nine days ago after a 9-month hiatus prompted by the ANC’s withdrawal on June, 20 1992 in the aftermath of the Boipatong Massacre – off kilter, one of the darkest moments in the country’s tumultuous history called for a leader with credibility, which De Klerk at that instance recognized himself to not have been! President of the Republic he may had been but as of a boomerang (as in the context of him initially speaking to Meyer – who in turn Barnard instructed to inform him ‘to speak to the old man’), De Klerk stepped back and let ‘the old man’ – Nelson Mandela, id est – lead!

The momentary role reversal commenced with a telephone call from the president to the leader of the African National Congress who likewise had retreated to his village of Qunu in the Eastern Cape for that Easter holiday. At this juncture, this tome’s author, Justice Malala, mentions that according to De Klerk – whom he personally interviewed – both (himself and Mandela) were “in shock”, with the two men agreeing that “the situation carried a serious threat of things getting out of hand.”

With the then NP leader deducing that “it was necessary to calm things down and to reassure people and to prevent activists from misusing this to disrupt the negotiation process.” He further informed Malala: “But more importantly, to prevent riots and situations where people’s lives would be under threat, and where race relations should become extremely tense.”

The maelstrom De Klerk, Mandela and citizens of the country, both Black and White found themselves being tossed about in on a religious weekend had been provoked by the unholy deed of a White man of rightwing leanings who – against the express instructions of a co-plotter, an abhorrent racist named Clive Derby-Lewis, to “don’t do it over the Easter weekend” – had, on what would turn out to be a fateful Saturday morning, driven all the way from his abode in Pretoria to Dawn Park on the East Rand, to cold-bloodedly shoot dead the SACP revolutionary in his driveway, and in full view of his horrified teenage daughter!

The assassin, a Polish émigré who’d relocated to South Africa in 1981, named Janusz Walus had, along with Derby-Lewis, sought to wreak mayhem across the country – thus putting paid to the transition to democracy De Klerk and Mandela were spearheading.

Hani’s address, along with Mandela’s, had been on a list of enemies of the apartheid system which had been provided by Arthur Kemp, a right-wing activist who wrote for The Citizen newspaper, who’d later at the subsequent murder trial seek to absolve himself of the crime by claiming that he did not know that it’d be used for a murder!

Caught in the act by Hani’s neighbour, Retha Harmse – an Afrikaner woman whose presence of mind led to the assassin’s arrest within half an hour of the murder – the remorseless Walus’ dastard deed promptly drew the condemnation of then Polish president Lech Walesa’s government which through its ambassador conveyed its “extreme outrage and sense of shame that a man of Polish origin was presumed to be the perpetrator of the assassination!”

Now, as the country teetered on the brink of racial conflagration, ‘the old man’ stepped up in the first of concerted efforts to douse the powder keg, in the form of an appeal for peace during an address to the nation on South African Broadcasting Corporation television, on the evening of the very Saturday of consternation. Describing Hani’s murder as a crime against all the people of ‘our’ country, in his speech Mandela spoke on to caution that “no one will desecrate his memory by rash and irresponsible actions.”

Mandela’s SABC appearance was then followed by the ANC’s National Executive Committee meeting on Easter Sunday at which – amidst venting of spleen amongst members – the liberation movement’s secretary-general and principal negotiator at Codesa, viz, Cyril Ramaphosa urged that the organization go “for the kill” by placing two demands on De Klerk’s administration to immediately set an election date and establish a Transitional Executive Council to oversee the run-up to the election!

Amid an environment of escalating racial tension evocative of philosopher, Jean Paul Sartre’s insinuation in his play, No Exit, that “hell is other people” – the calamitous situation was contextualized through words emblazoned onto the t-shirt of one of the leaders at a post-assassination rally in Katlehong which read: “You cannot die alone. They must also die.” Among victims of the broad expression of anger would be a handful of Whites who included two men who were set alight and a third who had part of his tongue cut out by an angry mob in Lwandle near Cape Town on Easter Sunday, and Alastair Weakley, a Grahamstown schoolteacher who taught isiXhosa and was a peace committee participant in his region, who, along with his brother, was killed in an ambush set up by a group of Black men at Port St. Johns on Tuesday, April 13.

Between the Saturday of the assassination and the Tuesday of Walus’ first court appearance for the crime, police reported 222 separate ‘unrest-related’ incidents – which encompassed killings committed both by opportunists and the police – across the country.

In response to the spiralling chaos, Mandela, of his own initiative, gave another televised address to the nation on Tuesday 13. De Klerk’s on the other side, was heavy-handed, with him summoning an emergency assembly of his State Security Council on the so-called ‘Hani’s Day of Mourning’ (Wednesday 14) which decided to deploy additional police and other security forces, and impose emergency regulations tantamount to outlawing the ANC. Conversely though, the SSC gathering unexpectedly acceded to the ANC’s demands of agreeing to an election date and establishment of a Transitional Executive Council (an ANC idea intended to seize power from the NP in the run-up to the elections).

The development would mark the expediting of the path toward the country’s very first democratic elections a year later from the moment!

Among hindsight’s retold in the tome is the incident whereby erstwhile heavyweight boxing champion, Muhammad Ali ended up being engulfed in teargas at a commemoration for Hani in the Cape Town CBD, during his tour of the country; Hani’s Dawn Park neighbour and friend, Tokyo Sexwale’s reckoning of how imperative it was during that period for the ANC to ensure De Klerk remained in power by avoiding a bloodbath and thus thwart securocrats and right-wingers’ doomsday aims; et cetera.

Barbara Masekela – who was then chief of staff in Mandela’s office – informed Malala that Mandela had one very clear objective throughout the period between 1990 and 1994: to hold free elections and achieve freedom for South Africans! “Nothing would divert him from that goal.”

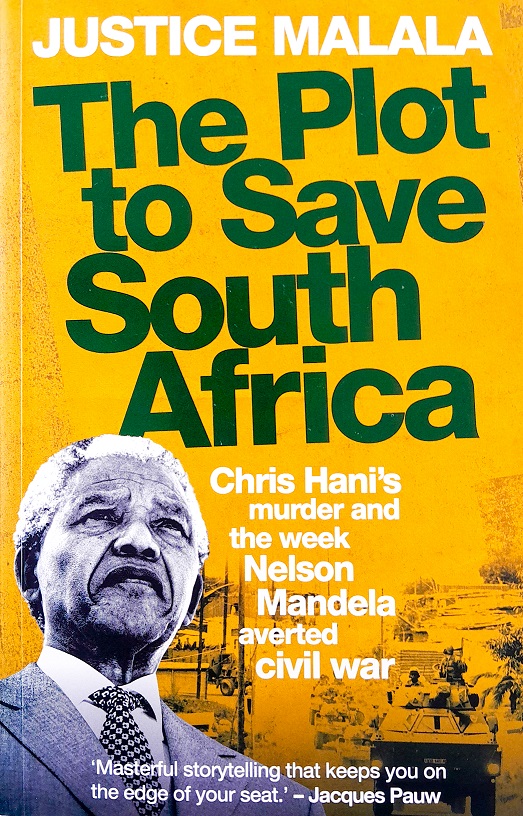

Author, Justice Malala was a 22-year-old student enrolled on a six-month journalism training programme on The Star newspaper when a news editor assigned him to, “Go out to Dawn Park now!”, on the Saturday morning of April 10, 1993 of Chris Hani’s murder.

The Plot to Save South Africa: Chris Hani’s murder and the week Nelson Mandela averted civil war, is his account of events which unfolded over nine days from the moment of the assassination as dark clouds gathered over a country then navigating its path towards a democratic dawn!

The Plot to Save South Africa is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers. Available at leading bookstores countrywide.

It retails for R320.