A TRAVELLING exhibition which looks at the history of German soccer powerhouse, FC Bayern Munich and the role played by the club and its members during the Nazi period, made its South African debut with its opening at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre in Forest Town on the evening of November 28, 2024 – after it first showed in 2016 at the Church of Reconciliation at Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial site and subsequently in over 50 locations in Germany, Austria and the USA.

Titled, FC Bayern Munich During National Socialism: Victims, Followers, Perpetrators, it was conceived and created in cooperation with the Church of Reconciliation at the Dachau Memorial and the FC Bayern Museum at the Allianz Arena in Munich, following on the findings of the Munich Institute of Contemporary History (an entity which deals with German and European history in the 20th and 21st centuries) which the club had, in November 2017, commissioned to a three and-a-half-year project named, “FC Bayern Munich and National Socialism”, which entailed the analysis of about 15 000 file scans, records and notes from almost 60 archives in Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Switzerland, France, Israel and the USA – to result in the first comprehensive history of a German football club during the Nazi dictatorship and, in the words of FC Bayern’s current president Herbert Hainer: “making a further contribution to the culture of remembrance – and to ensuring that history does not repeat itself.”

The display explores the fate of club members who were deported or fled (83 alleged to have forced to flee, 27 members alleged to have been murdered, four to have committed suicide – with three Jewish members fleeing to Johannesburg) from Germany for being Jewish or politically opposed to the Nazi regime.

Their geographical paths are traced on a map of the world – with nine biographical portraits, which include those of honorary club presidents Kurt Landauer and Siegfried Herrmann, narrating the story in detail.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, many football clubs were reluctant to exclude Jewish people. However, in 1933, the club did sign the “Stuttgart Declaration” that committed itself to the removal of Jews from sports clubs, along with 13 other German football clubs – resulting in the club excluding its Jewish members henceforth. Although there was no enforcement of this exclusion, many Jews were wary of the state of their club, resulting in 41 leaving between February and November 1933.

Between 1933 and 1945 more than half the officials in FC Bayern club management were also members of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (the official name for the Nazi Party) – even as the club held onto its Jewish members publicly. Among such members were those who were followers or perpetrators of Nazism such as Josef Kellner, a dedicated Nazi official elected as club leader in 1938 and Adolf Fischer who was club president from 1953 to 1955, and was guilty of Nazi plunder by enriching himself as co-founder of the Eidenschink Bank through the forced sale of Jewish companies.

The exhibition presents the biography of Landauer – the club’s Jewish president who survived the Holocaust – along with those of numerous other Jewish club members who likewise became victims of the Nazi ideology. An extraordinary personality in FC Bayern’s history, Landauer became president of the club for a total of 18 years – having been a member and player from 1901.

A visionary entrepreneur who repeatedly bailed out the club through his reparation money, he was elected club president for the first time in 1913, with the outbreak of World War I, forcing him to quit, only to return for a second spell from 1919 until 1933 when he was forced to resign. Having had four of his siblings killed by the Nazis, on the day after Kristallnacht, Landauer was arrested and incarcerated at the Dachau concentration camp along with 19 former Bayern Munich members and a thousand Jews – where he was released 33 days later, on account of having fought in World War I, and thereafter fleeing to exile in Switzerland.

In 1947 he returned to Germany and became club president again until 1951.

Post-World War II, his legacy became lost with club publications claiming that he had to leave Germany “on political-racial grounds,” according to Dietrich Schulze-Marmeling, the author of the 2011 tome, Der FC Bayern und seine Juden (FC Bayern and their Jews), who pointed out that because of having been a Jewish club with a Jewish president and a manager prior to the war – FC Bayern was targeted by the Nazis. Such a past became forgotten in the post-war years with the word ‘Jew’ assiduously avoided until the then West German society started to revisit the Holocaust in earnest from 1979, informed Schulze-Marmeling.

With renewed interest in the Landauer era and the FC Bayern leadership unsure as to how to react, it once got to a point where the club’s then general manager, Uli Hoeness, fobbed off an inquisitive reporter by saying he “wasn’t alive at the time,” and vice-president, Fritz Scherer admitting that the club did not want to emphasize its Jewish roots for fear of “negative reactions.”

Siegfried Herrmann’s biography is equally notable, having him rising from being a reserve player for the club to ascending to president after Landauer’s forced resignation on March 22, 1933.

Having been responsible for banning Adolf Hitler from speaking in 1925 whilst head of the Munich police department’s so-called political leadership, he fell into disfavour with the National Socialists due to his career position as an inspector general. After the Nazis takeover, he was immediately demoted.

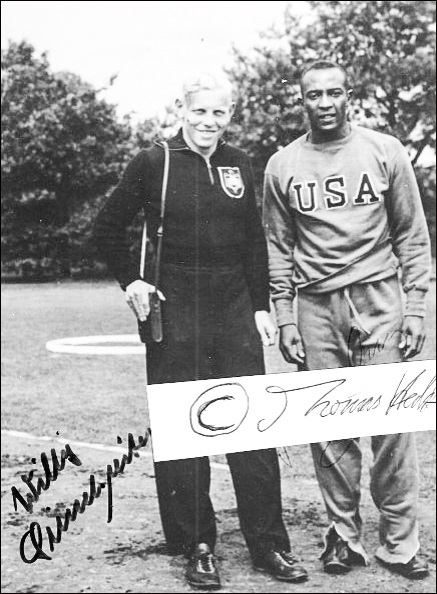

Discredited as a Judenklub (a derogatory label) by the Nazis, in 1934 FC Bayern players got embroiled in a brawl with Nazi brown-shirts and in 1936 the club’s winger, Willy Simetsreiter made a point of having his picture taken with Black American sprinter Jesse Owens (a tableau which features in the display), who enraged Hitler by winning four gold medals at the Berlin Olympics.

In 1943, players – to the Gestapo’s chagrin –waved at the exiled Landauer, after a friendly match against the Swiss national team in Zurich. Elsewhere, club captain, Conny Heidkamp, once hid Bayern’s silverware when other clubs heeded an appeal from Reichsmarschall Herman Goring to donate metal for the war effort.

The curator of the FC Bayern Museum at the Allianz Arena Fabian Raabe expounded: “the exhibition enables communities to discuss, learn and talk about the perspectives of the victims, the roots of Nazism and to make sure that this will never happen again.” Raabe further mentioned the Rot Gegen Rassismus (Red Against Racism) campaign – the club’s initiative which aims to stand against all forms of intolerance, abuse and exclusion. He marvelled, “what a strange combination: A German soccer club with its own exhibition, about its victims, perpetrators and followers during the time of Nazism.”

One of the images limns the club’s nonagenarian fan and Holocaust survivor, Abba Naor speaking to the youth players and coaches. Asked what forgiveness and reconciliation meant to him, during a 2022 visit to FC Bayern Munich, Naor answered that “one cannot only live in the past – there is also a future,” – adding that “sport is the best way to get to know people.”

FC Bayern was founded by a Berlin soccer enthusiast named Franz John and his 16 comrades-in-arms in Munich on February 27, 1900. It is one of the clubs with the most members in the world: 360 000 official members and 314 000+ Fan Club members – as well as 4 000+ Fan Clubs worldwide and 490+ international Fan Clubs.

Nicknamed Die Roten (The Reds), the six-time European Cup/UEFA Champions League winners (a continental competition at which they regularly compete against fellow elite clubs such as Real Madrid, Manchester United, AC Milan, Paris Saint Germain, et al. – they’re Germany’s most successful football club.

At the exhibition’s launch, the German Ambassador to South Africa, H.E. Mr Andreas Peschke, extolled – in Zulu – how a club consisting of eleven nationals in one team “I hlanganisa abantu” (brought people together), with the Director of the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre, Tali Nates, thanking Raabe for visiting for the opening.

After Raabe had gifted the ambassador a signed FC Bayern replica jersey of current player, Thomas Muller, and Nates, one of goalkeeper, Manuel Neuer – he treated attendees to a walkabout of the exhibition inside the JHGC’s Hall of Light.

Image provided (Willy Simetsreiter made a point of having his picture taken with Black American sprinter Jesse Owens).