“WHAT IS wrong with you? Have you not seen what’s happened?

We’re fighting Nazis.,” erstwhile Israeli prime minister Naftali Bennett, rebuked a British Sky News television anchor during an October 13, 2023 interview in which the latter enquired about the effect the Israeli government’s closure of the Gaza Strip would have on vulnerable Palestinians.

Four days earlier, Israel’s defense minister had announced a complete siege on the enclave – considered the largest prison on Earth –in which he had avowed that “there will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed.”

Bennett’s application of the description Nazis in reference to Palestinians appears to be Israeli bureaucrats’ deliberate choice of tag considering that a few days later on October 17, Israel’s current prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu would also use it when he referred to Hamas as “the new Nazis”, and thereafter on November 27, Israel’s finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, when he declared that “there are 2 million Nazis” in the West Bank.

Further to such a label, comparing October 7, 2023 (the fateful day of Palestinian organization, Hamas’ indiscriminate attack of Israelis) to a “modern-day pogrom”, as ten American Jewish organizations labeled the day, or, ‘the Holocaust’, as Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, Gilad Erdan, invoked when he told the UN Security Council that “entire Israeli families were turned into smoke and ash – no different than the fate my grandfather’s family met in Auschwitz” – is calculated to transform Palestinians from a subjugated people into the reincarnation of the monsters of the Jewish past whilst preserving Israel’s innocence, argues Peter Beinart, the author of this tome.

Israel’s hardline blockade of Gaza (Israel controls all access into it by air and sea as well as two of the territory’s three land crossings) and Operation Swords of Iron crackdown whose horror on Gazans will echo for generations, compels Jews to tell a new story as well as offer a new answer to the question: What does it mean to be a Jew? – argues the author, an American Jew who spent several of his formative years living in apartheid era South Africa.

After Gaza, where Jewish texts, history, and language have been deployed to justify mass slaughter and starvation, Beinart imagines an alternate narrative, which would draw on a different reading of Jewish tradition. In his view, one story dominates Jewish communal life: that of persecution and victimhood.

Beinart opines that for generations, Jews in Israel and the diaspora have built their identity around a story of collective victimhood and moral infallibility reminiscent of the narrative presented by Afrikaners who once believed themselves to be menaced by Black South Africans and Britain and the rest of the hypocritical West – hence their implementation of apartheid, even as it rendered them pariahs.

Beinart writes that many Israeli Jews view integration with Palestinians as suicide today just as – noted the journalist Allister Sparks – White South Africans equated racial integration with national suicide.

Regarding the alluded to victimhood, a chapter titled The New New Antisemitism, for instance, narrates instances about Jewish and Palestinian students’ experiences at US universities, at which hostility to Israel became so pervasive that Zionist students felt like ideological pariahs on one side, and pro-Palestine students (some of whom are Jews, ironically) were criminalized on another side.

Even as Netanyahu demonized Palestinian students and alleged, in April 2024, that “anti-Semitic mobs have taken over leading universities” amidst reported attacks on Jews on US campuses (which he described as resembling German universities during the Third Reich) – there had also occurred spates of instances whereby Palestinian and pro-Palestinian students and faculty endured much more violence than they had inflicted.

A study found that anti-Semitic incidents tend to spike around the world when Israel’s actions produced a global outcry – with other separate studies finding that when Israel kills more Palestinians, Jews around the world report more discrimination and abuse.

(Such a finding resonances with Israeli scholar, Limor Yehuda’s observation that countries that practice “political exclusion and structural discrimination” are far more likely to experience “civil wars”.) On a massive scale, in the nearly four months between October 7 and January 30, 2024, the FBI opened three times as many investigations into hate crimes against Jews as it opened in the four months preceding the attack.

Elsewhere across the read, Beinart noted that the organized Jewish community in Israel and across the world is working to smear and intimidate the world’s leading human rights organizations and international courts – a case in point being Jewish Zionists’ opposition to South Africa’s government’s International Court of Justice case to hold Israel accountable for the genocide against Palestinians.

Israel rejected warrants of arrest for war crimes against humanity the International Criminal Court issued on Netanyahu and Israel’s then defense minister Yoav Gallant on November 21, 2024 – to which Netanyahu’s office responded: “The “State of Israel denies the authority of the International Criminal Court in The Hague and the legitimacy of the arrest warrants.”

In October 2024, it declared UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres persona non grata, which the entity’s spokesperson regarded as “one more attack on UN staff” – which include 258 UNRWA (the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian refugees which provides aid to Gaza’s 2,2 million) staff members who’ve been killed by Israeli airstrikes since the beginning of the war.

As of September 22, 2024 the current war (which Israel resumed on March 18, 2025 after a hostages-and-prisoners exchange and armistice between Itself and Hamas on the Gaza Strip had taken effect from January 19, 2025) has left around 6 percent of Gaza’s population injured or dead – with eighty years estimated as the time it would take for the Strip’s reconstruction.

Amnesty International’s Secretary-General Agnés Callamard warned that if Israel can destroy Gaza with impunity, it will leave “international law likely in its death throes and nothing yet to take its place save brutalist national interests and sheer greed.”

Beinart mentions that he’s often been told that if Palestinians weren’t so murderous, rejectionist, incompetent, and pigheaded, they would have their own country by now. Yet every day, the very same Israeli Jews who are deathly afraid of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank place themselves in Palestinian hands in the form of Arab Israelis who comprise 25 percent of Israel’s doctors, 30 percent of its nurses and 60 percent of its pharmacists – sans fear of the possibilities of botched surgeries being performed on them or of being administered poisoned medication.

Once regarded as among Israel’s prominent American defenders, ‘twas eventually when Beinart visited Palestine – which only occurred when he was in his forties – that he realized the depths of the dehumanization he’d been carrying inside and gradually as his defensiveness subsided did he feel himself being remade.

He’d been surprised by the sophistication, quirkiness and normalcy of the people he met. For an individual who’s mindful that in establishment Jewish circles, supporting Israel is depicted not as a political choice but as an inherent part of being a Jew – Beinart confesses that Palestinians changed his understanding of what it means to be a Jew. “I’ve struggled with the way many Jews – including people I cherish – have justified the destruction of an entire society,” he revealed.

He urges that the weight oppressing Palestinians imposes on Jewish Israelis and indirectly on Jews around the world, can be lifted.

“This book is about the story that enables our leaders, our families, and our friends to watch the destruction of the Gaza Strip and shrug.

My hope is that we will one day see Gaza’s obliteration as a turning point in Jewish history,” he exhorts. Beinart appeals to fellow Jews – to whom his offering is directed – to grapple with the morality of their defense of Israel.

Peter Beinart was born in the United States in 1971 to Jewish immigrants – his father was an academic at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and mother, the head of a human rights film programme at Harvard University – from South Africa.

A professor of journalism and political science at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York – Beinart is also a non-resident fellow at the Foundation for Middle East Peace.

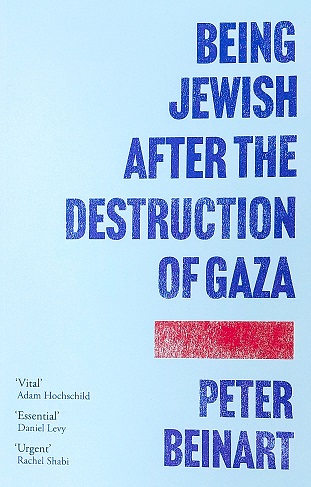

A trade paperback, Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza is published by Atlantic Books and distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R435.