“I LIKE nonsense some times, but I like common sense more.

I do not care to protest against apartheid. I am interested solely – as a human necessity – in ending the pigmentocracy of South Africa.”

This observation was articulated by Henry Nxumalo, the 1950s Drum magazine reporter who went by the moniker, ‘Mr Drum’ – yet it could as well had been declared by his then colleague, viz, William Modisane, popularly nicknamed, ‘Bloke’. Whereas Nxumalo was an intrepid investigative journalist at the seminal publication, Modisane was the urbane intellectual closer in outlook to the almost mocking cogitations of yet another colleague, the self-styled, Can Dorsay von Themba.

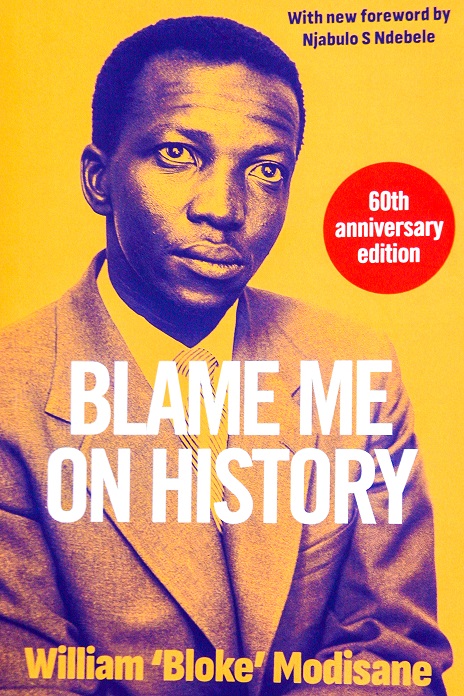

Blame Me On History, the 60th anniversary iteration of the book initially published in 1963, will, according to the foreword by writer, Njabulo S Ndebele, “expose our raw pasts which are still present as unacknowledged antecedents.”

Ndebele’s interpretation of Modisane’s apartheid heydays observations enunciate also upon the unfortunate socio-economic condition the majority of South Africans still find themselves trapped in – post-1994!

Official segregation might no longer be permissible, yet the yoke of classism, poverty, homelessness, crime – inter alia – still persist, reminiscent of the very circumstances which prompted Modisane and other Blacks to elope from their nativity in a quest for acceptance as well-intentioned humans.

Bloke’s Sophiatown, the location his account is mainly based in, was a crime-infested overcrowded slum aeons afore grand apartheid’s bulldozers rumbled through to lay it into a desolate landscape at the tail end of the 50s. It was, to a scholar of the era, a dichotomy to the romanticist monochromatic imagery depicting dancehall gaiety, cravat-&-fedora donning gangsters in big and glistening American convertible automobiles, bikini-clad lasses, et cetera, recorded by his colleagues, Jurgen Schadeberg, Peter Magubane and Bob Gosani.

Modisane’s was a homicidal place which accounted for Nxumalo’s life in addition to those of his father’s and countless others at the hands and knife blades of brazen hoodlums!

“You cannot protect all the screaming noises of Sophiatown,” an acquaintance warned him once after he had come to the rescue of a woman he had heard screaming on a street one evening. She had been accosted by a would-be rapist.

Pending another instance, his proclivity of attending to the screams of strangers almost cost him his life when he found himself facing the revolver of Lelinka (this writer came to learn that his name was Laluki), a member of the Americans gang, outside the Odin Cinema – after he had reprimanded the gangster for harassing a young lady pending a show. Whilst earning his keep as an usher, he had heard her scream and upon investigating, came across her and the feared figure engaged in a ‘compromising’ position amidst the darkness – with the ‘knife-happy rough-house (his own description) taking umbrage to his nosiness: “Just open your mouth, Bloke – open your mouth and I’ll shoot you,” the gangster postured menacingly.

The narrative taking the reader on a nostalgic excursion of the nook and cranny of the freehold neighbourhood where races – African, Asiatic, Chinese, – resided cheek by jowl but presently, in the Winter of 1958, laying flattened by Group Areas Act-enabled bulldozers, it dawned upon Modisane to effect his own exit from the land of his birth!

The rubble he passed laying strewn around whence he was sauntering stuck out as a morose reminder of what used to be of a cosmopolitan location now only persisting upon memory.

“Something in me died,” he averred, “with the dying of Sophiatown!”

With his marriage to the granddaughter of celebrated author, Sol T Plaatje, all disbanded and a close acquaintance such as Es’kia Mphahlele already having departed into exile – the impetus remained with him to take flight away from the inhumane system of racial segregation!

Granted, he had previously been presented with an opportunity to put a great distance between himself and the National Party’s bigoted fiefdom, when a White American couple offered him a job in California.

That, after Modisane had expressed, a yearning to emigrate with his family to any place which would spare them from the ignominy it was subjected to on a daily basis. It wasn’t to be!

An analysis deeper into the paperback partially reads akin to George Orwell’s exploration of pre-World War II sociological circumstances of the working class in parts of England – as expounded upon in, The Road to Wigan Pier. Offering statistics-backed insight as appertained to the average African family’s placing within the Gini coefficient barometer of the era, Bloke draws his reader to the preposterousness of White South Africans expressing surprise at the prevalence of malnutrition amongst Africans – simultaneously whilst being aware of the deliberate low salary cap government legislation had imposed onto the racial grouping.

Describing the privileged grouping’s mockery of the disadvantaged’s eating habits (read the staple diet of mealie meal porridge) as ‘a dirty joke’ – he equated its antipathy to the naïve utterance of Marie Antoinette’s ‘let them eat cake!’ In the final chapter the suave raconteur recalls the moment he departed from Verwoerdian South Africa.

Whilst awaiting a train to latter-day Botswana at Park Station, himself and fellow scribe, viz, Lewis Nkosi, had hopped along to a kiosk to purchase cigarettes whereupon they were met by the recalcitrance of a duo of Afrikaner women. What next transpired was literally a bitter parting shot between a deemed as a ‘nonentity’ and a hardened ‘European’, indicative of the prevalent colour determined attitudes of the time: “If you don’t mind, I want cigarettes,” requested Bloke with requisite humility. “Can’t you wait?” bellowed the riposte from one of the women. “No, I can’t wait,” retorted the author. “Then get out – get out, cheeky Native!” barked the missus.

From the then Bechuanaland, Modisane proceeded on to Europe in 1959 where he dabbled in acting. He settled in Dortmund, West Germany in the early 1960s, where he died at the age of 63, in 1986.

Published by Jonathan Ball Publishers, Blame Me On History, the revised edition is available at leading bookstores countrywide and retails for R280.00