THERE’S a phrase attributed to British wartime leader, Winston Churchill which has long done the rounds to the effect that, “history is written by the victors” – which implies that our understanding of history isn’t complete or objective but tends to privilege the version of events of those in power, or even those who documented it!

And few are as contentious as the Battle of Blood River which pitted Boer Trekkers (Voortrekkers) against amaButho amaZulu (Zulu regiments) on December 16, 1838.

An incident veiled in mythology, it remains one of the most politicized in South African history – with Afrikaners viewing it as a dispensation from God to rule the country, and an opposing view from Zulu historians disputing many elements of the narrative as Afrikaner propaganda!

It continues to expose the fractious perspectives prevalent to this day, with even President Cyril Ramaphosa on one side once entering the fray during a Day of Reconciliation speech in 2019, by describing the Voortrekkers as invaders and the amaZulu army as freedom fighters – and some Afrikaners on the converse side of the country’s political and racial divide excoriating his claim as a “criminalization of Afrikaner history”, as well as being tantamount to the nonchalant idiocracy of a demagogue and the majority Blacks of South Africa!

Contextual to this review, it is mere coincidence that the phrase is linked with Churchill, considering that he himself also partook, as a lieutenant, in one of the internecine wars which occurred in colonial era South Africa, viz, the Anglo-Boer War. Now, another Briton, a historian named Ian Knight, has also entered the fray regarding the narrative around that battle through his authorship of the tome, Blood River 1838.

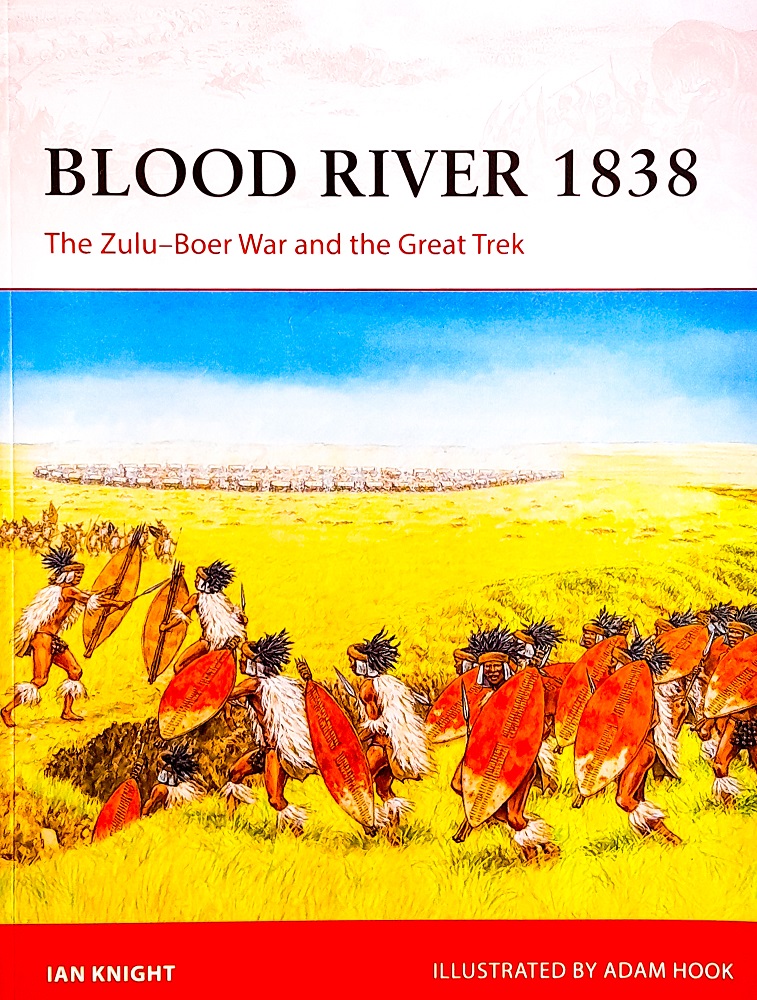

Acknowledged as a leading authority on the colonial campaigns of the Victorian Empire – which incorporated when British settlers arrived and set their roots in the then Cape colony and Natal during the 19th century – Knight’s version of the battle is accompanied by the illustrations of Adam Cook, a contributor credited as specializing in detailed historical reconstructions.

Knight’s narrative is riddled with application of descriptions such as: “subject to heated debate”, “it seems”, “perhaps”, “probably”, “contested”, “disagreed”, etcetera – indicative of an account based upon a combination of imagination, speculation, and referencing from other historians’ accounts of the event. Revealingly, the dearth of statistics from the side of amaZulu in his account are glaring – considering that his and those of other historians aren’t eyewitnesses’ accounts! Thus, his version of the event has to be ruminated with one’s critical volition.

Comprising of a chronology of events leading up to the battle; background of the opposing commanders and combatants; opposing strategies; aftermath of the war – as well as sketches, photographs and illustrations ranging from regalia and weaponry utilized, to battlefields onto which much blood became shed – following are excerpts gleaned from Knight’s account of an event purported to had unfolded between 04:00–13:00hrs of December 16, 1838: Dawn broke, and by about 06:30 the mist began to lift on a clear, bright, windless day, giving the Trekkers inside the laager their first unsettling sight of the left horn (of a Zulu impi) already in position to attack.

As soon as it was light, the Zulus rose up, drummed their spears on their shields and ran straight at the wagons. As they reached within 20–30 yards of the wagon wall, the defenders (Boer Trekkers) opened fire, pouring a great barrage of shot and lopers (slugs used instead of single bullets) into the Zulu ranks at close range.

Pretorius had instructed his men to fire in groups, one section firing as another reloaded, thus keeping up a rolling fire, whilst the cannon fired canister shot improvised from musket balls and scrap metal.

The shock of the fire was so great that the Zulus withdrew, only to regroup and charge again across a ground now littered with bodies. Although the iziThunyisa (a detachment of Zulu warriors mounted on captured Boer horses and armed with captured Boer muskets) seem to have hung at a distance around the laager, they fired at too great a distance to be effective. Their officers directed them instead to move past the southern face of the laager and pour into the donga on the southern side, but the banks were too steep to allow them to climb out easily and the donga soon became congested with a press of warriors who could hardly move.

Pretorius, spotting his opportunity, called on volunteers to make a mounted sally. They rode out over the open ground covered by the first attacks, and lined the banks of the donga, firing down into the warriors below.

Portraying another facet of the conflict the author continued thus: the right horn (of amaButho) moved upstream with the intention of encircling the laager to the north. Pretorius saw them coming and his mounted men, still outside the laager, lined the bank and shot the Zulus down mid-stream.

By noon, the Zulu attacks had no apparent hope of breaching the laager’s defences, some of the amaButho began to regroup with the intention of withdrawing. Pretorius gathered 160 of his men who mounted up. Splitting into two parties, they turned left and right, shooting any wounded Zulus.

Many warriors threw themselves into the river. Once across the river, the Zulus fled across the flats.

Pretorius himself had a narrow escape when one warrior turned to stab him, cutting his hand.

Knight further narrated that the plain on both sides of the river was littered with remains of Zulu combatants, with so many killed in the hippo pool that it seemed like a sluggish pool of blood. After the battle, continued the historian, Pretorius assessed the Zulu casualties at no less than 3000 men.

In return, not one of the Trekkers had been killed and only three were wounded.

Andries Pretorius (a 40-year-old farmer) had assembled a fighting kommando comprised of 464 Trekkers armed with flintlock and percussion types (firearm varieties), with himself in command and backed by six further commandants; a Calvinist minister named Sarel Celliers who together with Pretorius allegedly drafted a covenant with God in which the Trekkers agreed to hold the day holy should they be granted victory; a trio of Port Natal settlers who included Alexander Biggar (a settler who was bitter at the death of his two sons during two separate skirmishes against amaButho), who brought along about 60 African auxiliaries armed with muskets.

Additionally, Pretorius is said to had brought along his ship’s cannon, along – speculated Knight – with another one or two cannon.

Pitted against Pretorius’ force was amaButho numbering probably between 10 000 and 15 000 (other informants estimate their number at between 25 000–30 000) – among whom were an estimated 200 mounted and muskets-armed iziThunyisa – placed under the command of Ndlela kaSompisi (a contemporary of King Shaka who led King Dingane’s army) and Nzobo kaSobadli, his second-in-command.

Each combatant of amaButho would had been geared up with isihlangu (regimental war shields which covered warriors from head to feet) and armed with iklwa (a long-bladed, short-hafted stabbing spear) and up to three light throwing spears.

Following are noted points of disputation regarding Knight’s version of what occurred: for starters, how is it conceivable that 464 plus Trekkers and settlers suffered no fatalities against an army of experienced warriors who vastly outnumbered them? Ought to one accept as fact that iziThunyisa could not have inflicted casualties against Pretorius and 160 men of his kommando who, according to Knight, at some point abandoned the safety of the laager and waded into a melee teeming with thousands of armed amaButho?

Since the wagon-wall proved impenetrable – again according to Knight – against repeated waves of amaButhos’ siege on it, didn’t any of the waves of spears thrown (as limned on a centerspread image inside the tome) into the laager’s circle strike some of the Trekkers sheltered within?

The Battle of Blood River had been a clash over land rights in Natal. Subsequently, the Battle of oPathe of December 27, 1838 between the Boers and amaZulu – at which the latter managed to repulse the former’s expedition – gave the lie to the assumption that Blood River had been a decisive victory for the Voortrekkers.

A paperback, Blood River 1838: The Zulu-Boer War and the Great Trek is published by Osprey Publishing and distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R350.