‘DON’T worry about Malema. It will be okay.’ A farmer out in the rural areas conveyed this assurance to the then recently inaugurated Vice-Chancellor of Kovsie (the University of the Free State) via an early morning phone call, upon learning that the then president of the ANC Youth League was due to visit the very first black rector of the institution, in order to hear why the academic decided to forgive four Afrikaner boys who humiliated five black workers by making them drink urine containing concoctions during an initiation-type ceremony held in the students’ traditionally white male Reitz residence on the UFS campus in 2007.

Never mind that the academic was yet to assume rectorship of the institution when the incident occurred in 2007 nor when a racially insulting video of the incident emerged in February of 2008 – upon his appointment on October 2009, he now found himself amid a firestorm prompted by his decision to foster apologies from the culprits, compensation for the victims, and reconciliation by all parties concerned!

That, in addition to the withdrawal of the university’s charges against the offenders, as well as an offer for the four – who’d by then been expelled – to resume their studies!

With headlines conveying his approach as forgiving the racist students and suggesting their return to campus, all hell broke loose as angry responses from some sections of society implied that he was the devil himself – with an unnamed ANC Youth League leader announcing that, ‘the rector must die.’

It was whilst thus besieged that the academic gathered encouragement from a letter – declaring that ‘forgiveness is not for sissies’ – of support from Archbishop Desmond Tutu. It was also during this uncertainty that Malema showed up on campus – with those baying for his blood vindictively interpreting the firebrand’s visit as him ‘coming to sort out the rector.’

Following is an excerpt of what transpired between the ANCYL entourage and the UFS vice-chancellor: ‘Prof can you explain to us why you forgave those boys?’ enquired Julius Malema, later interrupting – whilst the rector was midway in explaining his decision – thus: ‘Prof, that’s enough. You made the right decision. It is better to have them here and re-educate them than to send them back into the community where they would be a danger to other black people.’

The response from Malema caused his then deputy, Floyd Shivambu to retort in horror: ‘No, I would not be let off that easily!’

To which Malema promptly riposted: ‘Sit down, the Prof has spoken.’ Surprised by the unexpected engagement with Malema, one of the rector’s colleagues would later inform him that Malema – who subsequent to the engagement with the academic had proceeded to address a horde which had gathered on the campus’ Red Square in anticipation of the outcome of his visit – had ‘told them you were right, that “he (the rector) is one of us”.’ At the moment of being overwhelmed by such an affirmative tone to Malema’s visit, the vice-chancellor rued that no number had been left for him to call the white farmer who had predicted the outcome!

The path to finding himself in academia had commenced tentatively, as hinted in the following conversation between the then Standard 8 high school pupil and a study mate regarding what people went to university for: ‘What do they do there?’ He had enquired, to which the mate, the very first person he knew to attend varsity then, responded: ‘Study.’

The unconvincing reply from his buddy drew this riposte from him: ‘but you just finished studying!’ Destiny would eventually have him emulating him to also study at varsity. If his supersmart peer was a pioneer, then he was the very first in his own family to do the same!

Said study mate, viz Lennie Dick, turned out to be one of two role models (the other being his Latin teacher at his alma mater, Steenberg High) who would become pivotal in what he refers to as transformations in his life from – not paying attention in class (he mentions classmates from his matric year 49 years ago recalling, during a 2023 reunion, how he once climbed on a table in class and proceeded to perform an imitation of singer, Percy Sledge whilst clinging onto a broomstick purported to be a guitar and then asking them, ‘do you dig me?’), obtaining disappointing marks in subjects, dabbling in tomfoolery during school hours, et cetera – to setting the reluctant student in him towards a course which with time would become beneficial first unto himself and subsequently, the sphere of education internationally.

Until the moment his then Standard 8 Latin teacher, Paul Galant, remarked that, ‘I have been watching you, you pretend you know nothing but actually you’re very smart’ – the sometimes truant pupil’s attitude had been that of straying outside his school’s perimeter during school hours to wander off to go watch movies on a Betamax video player at a classmate’s home; displaying a lack of interest in education whilst being madly attached to soccer (on more than one occasion, he had to suffer hidings meted out by his mom for losing his Bata Toughees shoes on a field after they’d been utilized as goalposts); disdain for sadistic teachers, et cetera.

‘It is hard to explain the reality of those times to young people when you are known as a distinguished professor. They think you were always smart,’ he’d later reflect.

The Dick and Galant-influenced transformation was to encourage him to own up to responsibilities such as immersing himself in books, studying hard for tests and exams, improving his marks, representing his school at a leadership camp, as well as in the 800m for the interschool championship at Green Point, etc.

With retrospect, he recalls Lennie enlightening him on a mathematical poser he couldn’t have an immediate grasp of owing to a teacher’s teaching method.

For a Cape Flats resident growing up in apartheid South Africa, his high school years coincided with exposure to what he refers to as ‘my real education’, enabled by teachers who used to expose his ilk to the radical poetry of James Matthews at Athlone’s Hewat teacher training college – about a period he discovered words attributed to George Bernard Shaw which went along the lines, ‘the only time my education was interrupted was when I was in school.’ His real education would segue on to ‘Bush’ (UWC) where it’d be augmented by ideologies such as Black Consciousness and theological expressions of which Struggle cleric, Dr Allan Boesak (who used to deliver stand-on-the-table lunchtime political lectures in the campus cafeteria) was the prominent exponent!

It is partially due to such influences that despite belonging to a race classified as Coloured, he adamantly asserts: ‘I am not, never was, coloured!’ Having persevered for an exhausting four years between 1975–1978, he graduated with a BSc degree and went on to teach biology at Cape high schools before studying abroad and thereafter returning to occupy leadership roles at South African universities.

It had been a remarkable life’s journey for the eldest progeny, of five, of a preacher, Abraham and a nurse, Sarah, who’d been born at picturesque Montagu and brought up in an evangelical family on the Cape Flats and inculcated in the tenets of a conservative evangelical church.

As an undergraduate at UWC, he’d preach on trains during the daily early morning commutes en-route to campus and would have his faith tested upon discovering rank hypocrisy on race and fellowship within his church in which coloured and white believers worshipped and dined separately.

The fixation with skin colour even extended to his future father-in-law’s objecting to his lightskinned daughter dating the dark-skinned him! The couple would nonetheless proceed to tie the knot and parent a son and a daughter – with the then young boy, Mikhail (named after the USSR’s president) becoming caught in the center of a diplomatic squall when overzealous bureaucrats almost prevented him from accompanying his parents on a visit back to their country on grounds that he was, by virtue of being born in the US, an American citizen. Recalled the then doctorate student at Stanford University: ‘after some back and forth, we were allowed to take the young American with us to our homeland.’

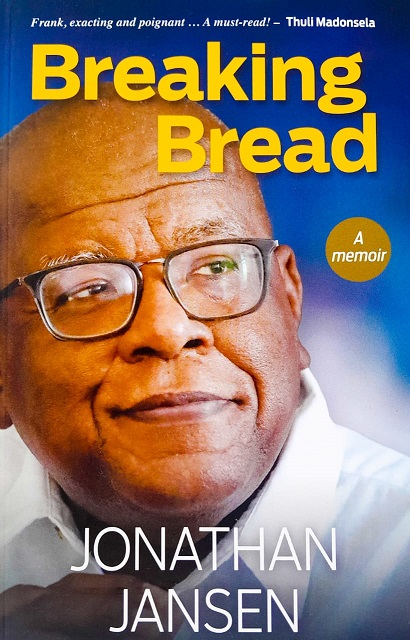

Those are select excerpts from the newly-published memoir of Professor Jonathan Jansen.

A trade paperback, Breaking Bread is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R330.