“YOU will have enough money to be incorruptible,” Dr Nthato Motlana, then the executive chairman of New Africa Investments Limited, persuaded Cyril Ramaphosa, the then African National Congress Secretary-General, to leave politics and go into business, back in 1995.

Pending that year, Motlana – who’d earned the nickname ‘Father of Black Economic Empowerment’ owing to his success in business – had set in motion a cunning plan through which he sought to build a ‘black Anglo American Corporation’ and wanted NAIL to be led by ‘trusted and credible African leaders’ such as Ramaphosa who, at the time, had reportedly expressed his willingness to join the entity.

Ramaphosa would be appointed NAIL’s deputy chairman after South Africa’s then president, Nelson Mandela – with Ramaphosa and Motlana present alongside him – had read a prepared statement to an assembled media corps in Cape Town on April 14, 1996 which partly announced that “it has been decided that Comrade Cyril Ramaphosa will be taking up a senior position in the private sector.”

Aged 43 at the time, Ramaphosa was quoted thus: “We need more black people at a senior level to begin to transform the economy, and I want to play a role.”

Motlana argued that even if Ramaphosa did have political ambitions – he’d still return to that later, as a wealthy man. (Ramaphosa would later maintain that going into business was his choice which in turn prompted him to propose to Madiba and the ANC that he be allowed to move into, while citing his ‘entrepreneurial spirit …surging to the fore’.)

In November 1996, NAIL became part of a consortium encompassing the National Union of Mineworkers and small Black businesses, which paid R2.6 billion for a 35% stake in Johnnic (an Anglo entity which at the time held the Johannesburg Consolidated Investments interests comprising 13.7% in South African Breweries, 26.4% of Toyota South Africa, 43.2% in Omni Media, 27.8% in food and beverage entity Premier Group and Gallagher Estate, inter alia) – which then had a market capitalisation of R8.5 billion.

Michael Spicer, an Anglo American executive appointed in the 1980s by the mining behemoth’s honcho Gavin Relly to develop contacts within the liberation movement, at the time described it as an ‘important symbolic deal’ to open up the racially exclusive economy.

Ramaphosa, dubbed ‘the new Randlord’ by some of the foreign press, became the non-executive chairman of its board, but the deal also proved to be his first taste of how difficult the business environment could be – as would be revealed in 2003 when he failed to shield the entity from a hostile takeover by Hosken Consolidated Investments, which also resulted in his ousting. (At the time, Ramaphosa’s biographer, Anthony Butler said Johnnic’s demise “came to represent the disappointed hopes of the first era of black empowerment in that it had been expected that the company would become the premier black company of its era.”)

Prior to the Johnnic loss, NAIL, with Motlana and Ramaphosa seeking involvement in mining, had also lost out on a further 35% stake, costing R2.9 billion, in JCI (which also housed Anglo’s mining interests) when it was outbid (with a certain Brett Kebble providing some of the finances) by Mzi Khumalo’s Africa Mining Group to a deal which included acquisition of the country’s then top gold mine, viz Western Areas. Critical of a ‘phoney’ type of business ownership achieved sans risk, AngloGold’s then chief executive, Bobby Godsell enquired: “How often do you think Cyril Ramaphosa has put his hand in his pocket to invest in businesses that he owns?” Godsell’s assertion would be corroborated when Ramaphosa conceded that, “Frankly speaking, I didn’t have skin in the game” – in reference to not having invested any of his own money in Johnnic – in the aftermath of the Johnnic takeover.

After an acrimonious end to his NAIL tenure in 1999, Ramaphosa proceeded to establish Millennium Consolidated Investments (which became Shanduka in 2004) in 2001, which acquired stakes in companies such as Alexander Forbes, Liberty and later owned the South African McDonald’s franchise. Shanduka would also acquire 1.2% of Standard Bank and 1.8% of Saki Macozoma’s Safika in a deal worth R5.5 billion – with China Investment Corporation in turn acquiring a 25% stake in it for a partnership with a Namibian power broker named Jürgen Kögl contended was purely for political and strategic reasons since Ramaphosa was in future likely to become the country’s president and investing in him was deemed a good decision at the time.

While Ramaphosa was exiled from politics for 16 years between 1996 and 2012, he was able to amass a fortune arguably unmatched by anyone making the transition from politics to commerce – wrote Pieter du Toit, this tome’s author.

When in 2012 he returned to politics as the ANC’s deputy president and of the country in 2014, Ramaphosa profited an estimated $200 million from Shanduka’s acquisition by Phutuma Nhleko’s investment firm, Phembani.

By 2015, he was regarded as the 42nd richest person in Africa with a fortune estimated at $450 million – a status, wrote Du Toit, not owing to him and others being shrewd businessmen, but rather to being favoured because of their links to the governing ANC.

It’s a puzzle then that Du Toit included Patrice Motsepe among beneficiaries of empowerment considering that the philanthropist amassed his fortune through the sweat-of-his-brow route when in 1997 he grabbed opportunity – despite Harry Oppenheimer’s scepticism – through his African Rainbow Minerals’ acquisition of seven of Anglo’s underperforming gold shafts.

The context regarding how Ramaphosa and ANC associates – who include Saki Macozoma, the Safika billionaire who ascribes his success to BEE and Tokyo Sexwale, the Mvelaphanda Holdings founder who by January 2014 New World Wealth consulting had named the third richest man in South Africa with a net worth of $200 million – became billionaires is linked to a September 1985 trip to Lusaka by a group of White South African business leaders led by Anglo American’s then executive chairperson Gavin Relly, for a meeting with the then banned ANC so as to influence political change in South Africa and ensure that later when the organisation was installed in government, it did not implement a socialist economy.

The Zambian visit – which the then President P W Botha had attempted to prevent – set in motion a coordinated and well-resourced plan by big business, particularly Anglo, to align themselves with the post-apartheid political elite, which also entailed bringing formerly excluded Black businessmen into the fold of big capitalism through ‘black economic empowerment’!

Relly returned from Zambia venting that “there’s no modern economic thinking in the ANC” and unimpressed by the liberation movement’s ‘fossilised’ economic ideas which were stuck in its 1950s Freedom Charter and Marxism-Leninism – oblivious to the rapid globalisation and modern economic thinking of the 1980s! He and colleagues, Spicer and Godsell (who used to face-off against Ramaphosa’s NUM at the Chamber of Mines’ bargaining platform in the 1980s) weren’t the only businessmen exasperated with the ANC’s ‘economic backwardness’ – with Black businessmen, Richard Maponya and Sam Motsuenyane’s pro-capitalist overtures rebuffed by the then incarcerated Nelson Mandela.

Spicer noted that only Thabo Mbeki – who held a master’s degree in economics from a UK university – was ahead of his comrades regarding the realisation of having to steer the post-apartheid economy away from socialism.

Godsell retrospected to the author that upon its return from exile, the ANC exuded a sense of entitlement expressed through the rationale that political power entitled it to economic benefit.

According to Kögl, who acted as an intermediary between business and the ANC, business’ acquiescence with the ANC extended to British magnate and Lonrho’s honcho Tiny Rowland purchasing a house in Sandhurst for Oliver Tambo’s family – incidentally the same suburb in which the Afrikaner mogul Douw Steyn owned a mansion, in which Mandela stayed for a period after his separation from Winnie in 1992.

Steyn had requested Dr Frederik van Zyl Slabbert – who operated a consultancy with Kögl – to introduce him to the returning exiles in return for availing his estate to their disposal.

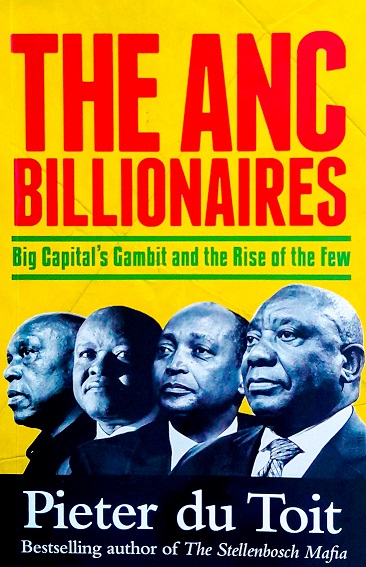

Du Toit’s read narrates the rise of ANC-connected billionaires by tracking efforts by big capital to influence the political transition.

Business wanted to survive and in order to do so, it had to make the Black elite owners of capital – even though they couldn’t afford it!

A trade paperback, The ANC Billionaires is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R330.