ONE snowing and cold day on January 14, 1943, a twenty wagon train carrying, among other passengers, 194 strafgeval (criminal cases), pulled to a halt next to the ‘Jews’ ramp’, a small platform, at Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp in Poland.

Also among the passengers, Jewish prisoners really, was a Dutch champion boxer from Rotterdam named Leendert Sanders who, along with his wife, Selli and their sons, Jopie and David, had been arrested on December 10, 1942 by the occupying Sicherheitspolizei (German Security Police) for going into hiding – in their own homeland for that matter – and taken to a Polizeigefangnis (Police Detention Centre) whose walls and doors had graffiti displaying a statement of defiance in Dutch reading thus: Hoe moeilijk de tyd, hoe zwaar ook de scheiding, we zijn weer een dag dichter by de bevryding (however tough the times, however hard the separation, one day we shall be closer to our liberation).

Prior to the Sanders family’s arrival at Stammlager Auschwitz (Auschwitz Main Camp), a destination they and other captives didn’t know of, they had momentarily been interned at Westerbork transit camp at which Leen, then classified as being untersucht (investigated), was kept in Schutzhaft (protective custody) in a punishment block on account of being regarded as a political prisoner.

(A Rotterdam boxing friend maintained that Sanders had been arrested ‘owing to his underground activities’.)

Preceding the family’s ordeal in the transit camp and ultimate arrival at Auschwitz, Leen’s parents, father, Josua Jakob, mother, Saartje and sister, Sipora – having travelled, also sans knowing their destination, by train from their homeland – had arrived at Auschwitz on a dark, misty and cold Thursday morning of October 15, 1942.

The small Sanders family group had been separated from other family members whose names were on List A no. 17, for Jewish transport to Westerbork.

Leen, who hailed from a Jewish family of five brothers and four sisters, had to, in 1928 interrupt his boxing career to do military service. Having refused to participate in the Berlin Olympic Games of 1936 held in Nazi-ruled Germany as a principled stance against the treatment of his people and residing in a country where Jews had to constantly defend themselves against the hostility of the Germany sympathizing National Socialist Movement (NSB) whose black-uniformed Weerbaarheidsafdeling paramilitary members considered them ‘the Netherlands’ downfall’ and were constantly fighting running battles with – in 1939, aged thirty-one, he became a reservist and part of the call up of twenty-five thousand Rotterdammers to the Netherlands army’s mobilization against the looming German invasion threat.

Deployed to the western Netherlands as a soldier, he was promoted to the rank of corporal. On May 10 of 1940, with the German invasion of Holland in motion, Sanders was captured during a battle which claimed the lives of twenty of his fellow soldiers and resulted in him ending up as a prisoner of war in German custody.

Five days later, the Dutch sovereign, Queen Wilhelmina announced the country’s capitulation.

Whilst in captivity, Leen managed to escape and returned to Rotterdam to a heap of bricks and debris which used to be his home. Placed on a surveillance list of the occupying Sicherheitspolizei (German Security Police) and residing in The Hague – Sanders was no longer a free citizen in his own country!

Immediately separated from his wife and sons upon their arrival at Auschwitz, Leen was promptly given a number, 86764 (Achtsechssiebensechsvier), which he had to memorize in German and by which he’d henceforth be referred – substituting his actual names!

Spelling out the rules to Sanders and fellow newcomers inside the camp, a block leader sternly reminded them that it was futile to attempt escaping – adding that the only way out for a prisoner was through the Kamine (the chimney), alluding to the structures discharging to the sky, the morbid residue from the incinerators constantly stuffed with inmates’ corpses!

One day, an SS (Schutzstaffel) officer who used to be a sports journalist recognized Sanders from past boxing matches he participated in, in Berlin and promptly arranged a work detail for the pugilist which would ensure that he’d be kept alive in the concentration camp – a lifesaving overture the very opposite of the death by gassing fate which befell his family a mere week after their arrival!

He now found himself assigned to the New Laundry Work Detail whose employees were spared from various forms of hard labour – and at which it was conducive to smuggle out items such as pullovers, shirts and socks which in turn could be battered for butter, sausages and cigarettes.

Such an activity, were a prisoner caught, was punishable by death!

Away from the atrocities occurring on a daily basis inside the camp, to assuage the bored Nazi captors, permission was granted for the erection of a boxing ring adjacent to ‘Dalli-Dalli-Allee’ (Look -sharp Avenue) and the staging of boxing matches featuring the prisoners on Sundays for their entertainment.

Camp Commandant Rudolf Hoss even gave permission for more matches of a high standard since unexpected visitors such as the Nazis’ top brass, viz, Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels and even the Fuhrer himself, Adolf Hitler, might attend.

According to the Fuhrer, boxing possessed the potential of moulding the ideal future young men of Germany. Although boxers were held in favourable regard within the camp and SS officers went about actively recruiting fighters for tournaments, participating in the contests would also mean life or death for them as was made abundantly clear to an Amsterdam pugilist by an SS officer who warned him that: “If you lose, you’re going to the crematorium!”

Conversely, victory meant extra food for the conquerors!

After Karl Egersdorfer, an SS officer in charge of the Haftlingskuche (prisoners’ kitchen) had earlier enquired from him: “don’t you want to be boxing too?” – Sanders grappled with the dilemma where winning could be as hazardous as losing, since as a Jew, the camp system was set up in such a manner that his death sentence could be carried out at any moment and SS officers might be angered by the result of a match such as wherein a Jewish boxer defeats an Aryan opponent – which was considered as Rassenschande (racial defilement) – and seek to exact revenge by condemning him to the Black Wall (a firing squad section).

His situation inside the camp changed for the better upon being approached by a Polish boxer named Kazimierz Szelest, who happened to be the kitchen storeroom kapo (a prisoner functionary), with a request to be trained by him for the All-weights Champion of Auschwitz title in exchange for being compensated with extra food.

Taking up Kazik’s offer, he was immediately permitted to relocate to a block for prisoners with privileged positions – a development he later noted thus: “you wouldn’t normally be sent straight to the gas chamber from there.” Referring to Kazik as ‘my saviour’, Leen mentioned that the extra food he got from him enabled him ‘to save a lot of human lives.’

His circumstance improved further when, in early February 1943, he decided to make a comeback to the ring after an absence of more than two years. From then on, Sanders participated in weekly boxing matches culminating in his annexing the All-weights Champion of Auschwitz title from Teddy ‘White Mist’ Pietrzykowski.

His status as a champion ensured continued survival of fellow prisoners, including Dutch women kept as ‘guinea pigs’ in Dr Josef Mengele’s experiment Block 10, since the food he ‘organized’ proved to be crucial sustenance for the debilitated among them who could otherwise be selected for the dreaded gas commission (chosen for extermination).

On January 18, 1945, Sanders and other detainees got evacuated from Auschwitz – only to be interned further at the Gross-Rosen and Dachau concentration camps and the Muhldorf external concentration camp and surviving a death train (Muhldorf death train) ride in which captives died from fights, cold and hunger!

Finally, on April 30, 1945 Sanders and his accomplices were liberated by American soldiers of General Patton’s army at Seeshaupt in Germany, from where he made it back to Holland.

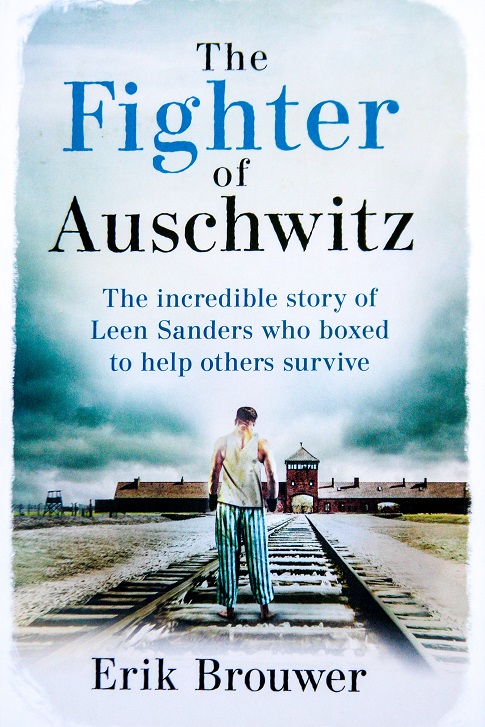

Penned by Dutch sports journalist, Eric Brouwer, The Fighter of Auschwitz is described as a testament to the endurance of humanity in the face of extraordinary evil!

A paperback, The fighter of Auschwitz is published by the Octopus Publishing Group and distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R260.