THERE WAS the time O Mais Velho (Portuguese for, The Elder) lied to the media corps that Tito Chingunji was alive – at a press conference at the 5-star Mount Nelson Hotel in Cape Town, in early February of 1992.

“Yes, of course, Tito is alive and well, doing his job as deputy secretary-general and looking forward to the election campaign,” The Elder (the figure otherwise known as Dr Jonas Savimbi) assured seasoned British foreign correspondent, Fred Bridgland, upon the latter’s enquiry of the whereabouts of the former’s UNITA foreign secretary.

A fabricated charge advanced the reason that Chingunji, inter alia – a youthly 36-years at the time of his brutal murder through bludgeoning with rifle butts by a Savimbi-sanctioned execution squad – had worked with the CIA to topple Savimbi.

The tragic slaying of the Angolan rebel leader’s head of bodyguard was another lie advanced by the warlord and the ultimate betrayal of a comrade-in-arms who had stood by him from colonial to post-independence Angola.

Not only was the handsome and bespectacled Tito’s life cut short – but those of his wife, Raquel (Savimbi’s niece who he had raped, made one of his concubines, and had sent to seduce and spy on Tito) and the couple’s three children – including his twin sister, Helena and her husband, Wilson, and their three children, as well as his only surviving brother, Dinho’s wife, Aida, and the couple’s three children!

The purging of the Chingunji clan didn’t cease with those as Savimbi, whilst retreating from an execution squad tasked with his elimination, ordered the callous killing (through being buried alive in a wild animal’s lair) of Ana Isabel Paulino – the woman Tito loved but who Savimbi stole (after posting Chingunji to Morocco on party duty and thereafter claimed as his ‘number one’ official wife, in the former’s absence) because of her beauty and sophistication.

Savimbi’s unabashed lie was uttered whilst he was on a South African official visit for pre-election (Angolan ones geared toward bringing to an end the long-raging civil war) talks with then president, FW de Klerk. Then, Bridgland had posed to the charismatic figure who insisted on being referred to by the title of a doctor despite never having graduated with a PhD: “Can you tell the international community whether Tito Chingunji is still alive?” The truth was that seven months before the Cape Town press conference, Savimbi had summoned his executioners and ordered them to kill Tito and every remaining member of the Chingunji family and some of its more remote relatives!

If those who read and are knowledgeable regarding the track of history reckon Pol Pot (Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge dictator whose excesses were exposed by the New York Times’ foreign correspondent, Sydney Schanberg’s revelations as depicted in the film, The Killing Fields) or Emperor Jean-Bedel Bokassa (the Central African Republic military leader who once ordered a selection of prisoners to be fattened – only for whose flesh to end up at a deliberate cannibalistic banquet) or Idi Amin Dada Oumee (Uganda’s most brutal despot in modern world history) were brutal – the reader only has to peruse through a chapter of Brigland’s recently released paper cover tome, titled, Witch burnings and other atrocities (1983 onwards), which accounts for a chilling saga which unequivocally earns Savimbi a spot amongst this rank of infamy!

On September 7, 1983, Savimbi summoned everybody to a ‘very important rally’ at his Jamba camp.

On a day subsequently remembered as Red September, O Mais Velho called out the names of women he claimed to be witches and had promptly condemned to death by burning alive in a giant bonfire. The beret-donning National Union for the Total Independence of Angola honcho justified the savagery by alleging that witches had been plaguing his movement, causing its soldiers to lose their lives pending skirmishes with its MPLA nemesis.

Those who perished on the dreadful day included children (because ‘a snake’s offspring is also a snake.’ – and the orgy, which in today’s terms could had been deemed patriarchal, even involved an act of great betrayal whereby the husband of a woman known as Clara Miguel ran towards her and kicked her as she advanced towards the fire, in a purported demonstration that he had nothing to do with his wife’s witchcraft! remarked.

Other than his magnanimous lies and betrayal, the exhilarating read also serves to unmask Savimbi as being ungrateful for lifelong loyalty paid unto him by those close to him – as demonstrated in the vanquishing of the Chingunjis (whose paterfamilias, Jonatao, had co-founded UNITA with him).

Wrote American foreign correspondent, Inge Lippman, to Bridgland, who she had introduced to Savimbi back in 1975, on hearing of the politician’s demise: “I can never forgive Savimbi for his murder. I do hope if there is any justice in this world, which of course there isn’t, the Devil will take care of Savimbi.”

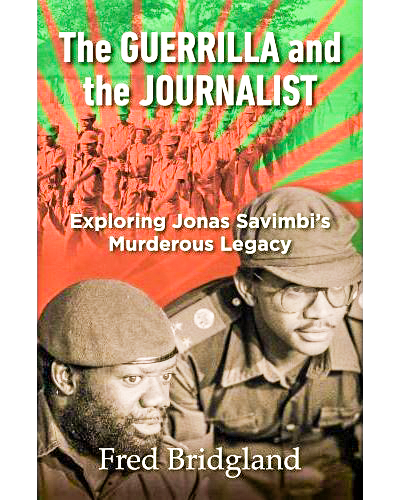

The guerrilla in the book’s title refers to Tito Chingunji, Savimbi’s head of personal bodyguard, who proposed that himself and Bridgland – the journalist, in the title – write a book on UNITA and Savimbi (titled, Jonas Savimbi: A Key to Africa and published in 1986.)

Fred Bridgland had started out as a member of the Anti-Apartheid Movement who, as a Reuters’ Central Africa correspondent based in Zambia flew into guerrilla-held Angolan territory on February 7, 1976 – subsequently to be introduced to the then 41-year-old Savimbi and his rebels.

The Guerrilla and the Journalist, a trade paperback, is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers and retails at R290.