‘THEY project a democracy in which the government, whomever that government may be, will be bound by a higher set of rules, embodied in a constitution, and will not govern the country as it pleases.’

The newly-elected President of the democratic Republic of South Africa, Nelson Mandela, uttered these words from the Cape Town City Hall on the Monday of May 9, 1994.

The ‘they’ the 75-year-old alluded to were the anchor documents – i.e. constitutionalism, the rule of law, good governance, respect for human rights and responsive and responsible government – he was committing his new government to adhere to.

Representing an ANC which had garnered 62% of the unprecedented polls of April 27 of that year, he went on to aver: ‘We place our vision of a new constitutional order for South Africa on the table not as conquerors prescribing to the conquered.’

Back in 1994 after the ANC had assumed governance amidst a groundswell of endorsement, there was no sign – at least according to Tim du Plessis, a journalist representing the White media who covered both South Africa’s apartheid and transition eras – that it would eventually turn out to be the organization at the centre of state capture and misrule.

Conversely, Stephen Ellis, author of External Mission, the tome on the history of the organization in exile, places the ANC’s fall from grace to the late 1970s and the 1980s during which organized crime took root within its ranks.

Ellis cites an ANC cadre who revealed: ‘some leaders were using ANC personnel and facilities to indulge in illegal activities such as drug smuggling, car theft and illegal diamond mining.’ ‘Smuggling convoys were even protected by soldiers from uMkhonto we Sizwe.’

Ellis further mentions that ANC leaders’ involvement extended to the smuggling of Mandrax in which new BMW and Mercedes-Benz cars were utilized to transport the drug and cash (which was concealed within the paneling) across borders – with the complicity of bent Southern African authorities.

An early indicator of what was brewing under the party’s rule would be the implementation of its policy of cadre deployment introduced during Mandela’s presidency, overseen, from 1998, by Jacob Zuma’s deployment committee and enforced by Thabo Mbeki during his presidential tenures. It would lie at the heart of the country’s failings during the ANC’s 30-year governance!

The system ensured that the party’s rent-seeking (the practice of individuals financial profiteering from positions in government and the public service) culture would flourish through the placing of cadres in all strategic positions in the state such as cabinet, civil service, agencies such as the National Prosecuting Authority, parastatals such as Eskom and mass media such as the SABC.

For all Mandela’s veneration and exhortation of ‘government not governing the country as it pleases’, corruption and avoidance of accountability became part of the ANC’s culture during his presidency – with opposition leader Tony Leon noting that: ‘Warning bells rang loudly during Mandela’s term but he did not do much to answer the alarm.’ Mandela: defended then Minister of Health, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma during the Sarafina 2 scandal in which she lied to Parliament regarding the source of funding for the R14.3 million HIV/Aids awareness play; defended cleric, Dr Allan Boesak, by calling charges against his misappropriation of funds ‘baseless’; was complicit in the cover-up of corruption claims against then Minister of Public Enterprises Stella Sigcau who was alleged to had been bribed by gaming mogul Sol Kerzner; dismissed then Deputy Minister of Environmental Affairs Bantu Holomisa from his cabinet and the ANC for ‘political indiscretions’; was embroiled in the R143 billion Strategic Defence Procurement Package arms deal (the first megascandal of a democratic SA which ended up in an ANC cover-up) ignominy!

An earlier basis of bickering amongst comrades was when the Reconstruction and Development Programme (through which the ANC promised its supporters the provision of millions of jobs and houses and piped water and electricity) was abruptly discontinued after two years due to being unworkable – and replaced with the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) macro-economic policy purposed to lay grounds for pushing down unemployment, inequality and poverty.

Presented to Parliament in June 1996, it precipitated a clash of ideologies and factions which led to Mbeki’s ousting 11 years later and gave rise to Zuma and the dismantling of South Africa by a cabal of political opportunists!

In Parliament, the ANC’s dominance commenced with the bulldozing of its diktats at the expense of opposition and minority rights. (From 1994, in his role as ANC Secretary-General, Cyril Ramaphosa compelled party MPs to sign a code of conduct which forbade any ‘attempt to make use of parliamentary structures to undermine the ANC’s decisions and policies’).

Much later, as state president, Ramaphosa would inform Chief Justice Raymond Zondo that ‘it is the party where power resides’ – upon the latter’s finding of cadre deployment to be ‘unlawful and unconstitutional’.

The promulgation of the Public Service Amendment Act in 1999 under Mbeki’s presidency expedited the deployment of ANC apparatchiks into every leadership position across the state as he, to quote IDASA’s Dr Frederick van Zyl Slabbert’s words to erstwhile Rand Daily Mail editor Allister Sparks, used ‘authoritarian and undemocratic’ methods to entrench his dominance and control of party and government – in order to realize his vision of a South Africa he intended to kowtow with the prescripts of the National Democratic Revolution.

Entrenched with his acolytes, at the helms of the party and government, Mbeki would go on to taint his legacy through his intransigence on the HIV/Aids crisis which resulted in an estimated 320 000 people (who included his then spokesperson, Parks Mankahlana and fellow ANC heavy hitter, Peter Mokaba) dying of the pandemic.

Elsewhere, his organization’s questionable influence in the tendering process resulted in its funding arm, Chancellor House, scoring R97 million from BEE partner, Hitachi’s R38.5 billion winning bid to supply Eskom with boilers for the Kusile and Medupi power stations – whose defects ultimately contributed to the stations’ cost overruns bleeding taxpayers to the tune of more than R120 billion each!

Post-Mbeki’s ousting by the Zuma faction at Polokwane in 2007, the ANC embarked on an epoch of corruption and misrule spanning a decade – commencing with the ‘recall’ of Mbeki as president, effectively a coup d’état, around September 2008; the dissolution of the Scorpions by caretaker president, Kgalema Motlanthe, on January 30, 2009; the introduction of a raft of bills such as the Broadcasting Amendment Bill which enabled the state’s interference with the SABC’s mandate, the Protection of State Information Bill intended to negate the influence of whistleblowers and the media, etcetera; tolerance of ‘tenderpreneurism’; the building of Zuma’s Nkandla homestead with public money, etcetera.

After 16 years out of mainstream politics and four months after lobbying, as a director of Lonmin platinum mine, government to intervene in a strike which resulted in the Marikana Massacre – Cyril Ramaphosa resurfaced as the ANC’s deputy president at its Mangaung Conference in December 2012, and was catapulted to head its deployment committee to which he pledged to do his damnedest to ensure the president’s plans succeeded.

Expanding his rhetoric, he promised: ‘we are going to get some of the best attributes coming through from our cadres, who will have total commitment to their service of South Africa.’

Alas, despite his committee’s regular changes to executive structures of parastatals such as Eskom, Transnet, PRASA, and the SABC – the interventions became key to their capturing by those beholden to the Guptas or other criminal networks.

Holding the position for five years, he was so powerful that if his team was unhappy with ministers’ proposed appointees – they’d be sent packing!

Ramaphosa is alleged to had been oblivious to the unfolding madness even as newspapers were exposing the criminal networks. ‘There were signs’, he admitted – but the ANC didn’t act!

No cadre did more to protect Zuma, and defend the ANC, and is responsible for the misrule of South Africa, since 2007 as Gwede Mantashe, and when investigative journalists published articles on ANC corruption, he dismissed them out of hand as ‘racist.’

On the Thursday of May 30, 2024 he cut an aloof figure whilst disconsolately scanning the results board at the IEC results centre at Gallagher Estate – which confirmed the ANC’s electoral decline to 40.18% in the May 29 polls.

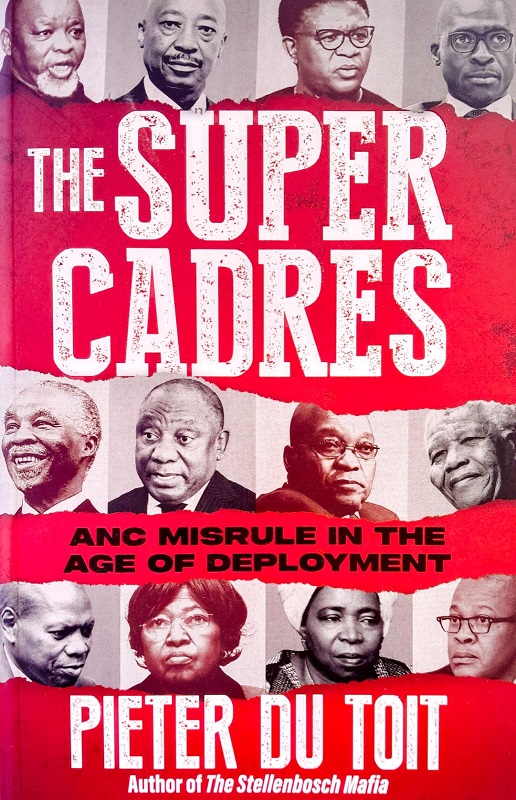

Author, Pieter du Toit is a journalist at NEWS24. His previous tomes, The Stellenbosch Mafia (2019) and The ANC Billionaires (2022) were best sellers.

A trade paperback, The Super Cadres is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R330.