SIXTEEN-year-old Sabreen found herself squashed upright among 400 hundred other people in a standing-only formation on a fishing boat meant to carry 100 whilst all around the tiny vessel the rough and chilly waters of the Mediterranean ocean caused it to bobble sporadically – resulting in the nauseating contents of a makeshift ablution container spilling onto the floor upon which herself and fellow passengers stood!

The teenager was braving the much dreaded dangerous crossing from an African coastline – in her group’s case, from around Alexandria in Egypt – desperately and hopefully for safe passage en route to Italy! A Yemeni left in limbo in a foreign country by an older sister who, upon being granted a visa three months earlier on, had departed for the US in December of 2014 to reunite with their mother – Sabreen (no family name disclosed), her patience finally worn out, eventually parted with $2000 she had convinced her mother to raise for passage to Europe, where she hoped to obtain a visa which would ultimately enable her to join the two in America.

Alas, the girl – a refugee from the then upheaval-ridden Yemen – who whilst young would often be heard saying, ‘one day I’m going to go to the US’, ended up never reaching the land of the free, instead, electing to get married to a man she’d met in a refugee camp in Holland. A Muslim travel ban announced by then President Trump would put paid to the sisters hoped for reunion! At some point Sabreen had remained rooted on the shore paralyzed with fear from the sight of huge waves before her shortly the daunting crossing – prompting a man who scooped her into the boat to rdeadpan: ‘there is no turning back!’

Along with her older sibling, Zaynab, Sabreen was a part of multitudes of refugees fleeing the turmoil which enveloped countries such as Egypt, Libya, Syria and Yemen as a consequence of the Arab Spring. Amidst a spate of indiscriminate bombings, killings and conflict among warring factions which resulted from the Yemeni people’s demand for the incumbent head of state – who’d been in power for thirty years – to step down, the sisters fled to Egypt, with the intention of ultimately linking up with a mother who had left them when they were around four and two years of age respectively.

Effectively orphans since their father had abandoned them when Sabreen was born, the duo had to fend for themselves varyingly subsisting in the care of a grandmother who died; an aunt who suffered a breakdown, and an uncle who ejected them from his Cairo house after Zaynab contracted tuberculosis. Their two-year sojourn in Egypt whilst awaiting visas would end when the US embassy approved passage to the United States for Zaynab – news the teenager who was about to turn 19 described as ‘the best birthday present ever’ – but to the heartbreaking exclusion of her kid sister, whose application was rejected!

About the time the sisters’ separation was unfolding, another young girl named Muzoon and her family had, for two years, been living under siege of war which had erupted in their native Syria in 2011 until her dad, in exasperation informed her, ‘even life in a refugee camp has to be better than this’, decided to flee with his family to the safety of Jordan – across whose border they walked through the night and onto a refugee camp. Once there, ensconced together in a small tent with seven other people and with plenty of time to kill – Muzoon began encouraging other girls to attend the camp’s school.

Encountering peers whose parents believed their daughters futures lay in marriage, and who reasoned that they wouldn’t be in the camp for long, she exhorted, ‘No one knows when we’ll go back to Syria! We could be in the camp for years.’ Her empathy would dissuade a girl of 17 from marrying a man in his forties her family had wanted her to. Averred Muzoon: I knew that early marriage would trap girls in a cycle of poverty and deprivation.

Away from Muzoon, another girl from the Yazidi community of Sinjar in northern Iraq named Nalja would find herself in a battle of wills with her father over her determination to become educated, converse to his – and that of the community – wish for her to become a housewife. Her obduracy resulted in her running away to the mountains for five days and her father not speaking to her for a year until he eventually relented and allowed her to go to school! However, her triumph would prove momentary as in August of 2014, ISIS invaded her village, abducting women, killing men and plundering in its wake – forcing her family of thirteen siblings to flee into the Sinjar Mountains where they were to spend eight days, never to return back home!

Unbeknownst to them – they had survived one of the worst massacres to befall the Yazidi (a religious minority neither Muslim nor Christian numbering less than a million people)!

The young women, along with their families, are part of 79.5 million people forcibly displaced worldwide – 25.4 million of whom are considered refugees. The girls’ narratives are of experiences which unfolded – and continue so – from Africa, Middle East, Asia to Latin America, Central and North America. They range from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Zambia, Uganda, Jordan, Syria, Yemen, Myanmar, Bangladesh – to Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, Canada and the United States of America.

From young Maria in Colombia suddenly having to flee violence which engulfed her innocent existence on her family farm, to Ajida, a Rohinga (a minority Muslim group in the majority Buddhist Myanmar) woman who, along with 300 people, fled into neighbouring Bangladesh after Myanmar soldiers and police raided, raped and pillaged through her village one night in 2017.

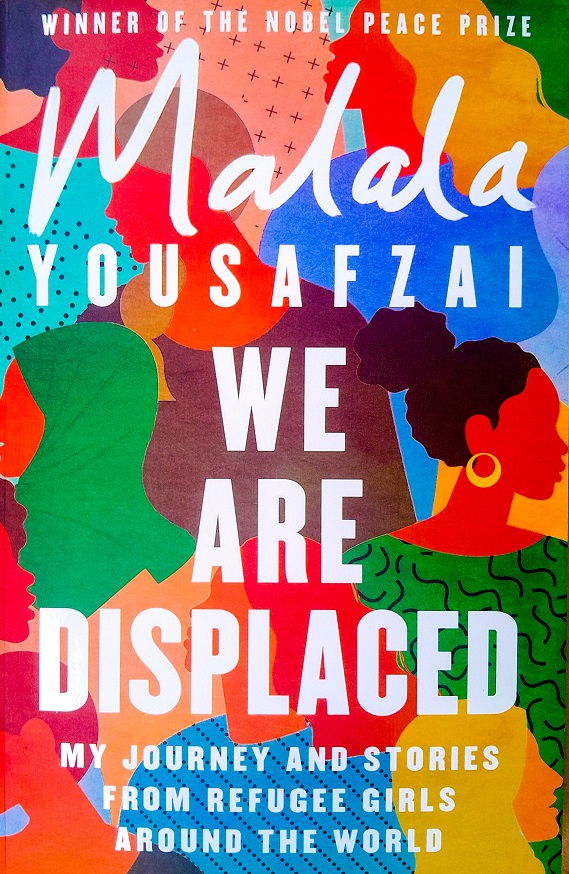

The writer who collated the experiences of the young women featured in this tome – having personally met them – viz, Malala Yousafzai, was herself, along with her family and more than two million other residents, displaced from her city, Mingora in the Swat Valley (once a vacation destination referred to as the Switzerland of the East) in a mass evacuation in May of 2009, whilst government troops engaged in skirmishes against the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan around the region.

Life as she knew it had suddenly been disrupted by the emergence of men who began preaching strict interpretations of Islam amongst which was their issuing of a decree on January 2009 for the closure of all girls’ schools – an act which affected 50 000 girls in her region who overnight lost their right to an education!

Passionate about education along with her father Ziauddin – who had built and administered two schools (with one being for girls) – her activism for female education and defiance of the intimidating men with long beards and black turbans would culminate in her being shot in the head by a Taliban gunman on a bus on October 9, 2012, when she was aged 15. It would be this assassination attempt, widely condemned around the world, which brought her to the world’s attention and prominence – with her progressing on to becoming, aged 17, the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize laureate in recognition of her efforts on behalf of children’s rights!

Inspired by assassinated Pakistan Prime Minister, Benazir Bhutto, and nominated for the International Children’s Peace Prize by Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu in 2011, Yousafzai co-authored I Am Malala, an autobiographical tome which details her life before the Taliban; the group’s rise and fall; the attempt on her life, as well as the surgery performed at a Birmingham, UK hospital to repair the damage caused by the shooting.

During her delivery of the 21st Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture in Johannesburg on December 5, 2023, Yousafzai mentioned – whilst slamming what she described as the Taliban’s ‘gender apartheid’ (in which the movement claims that oppressing girls and women is a matter of religion) in Afghanistan and simultaneously urging for countries to deem it a crime against humanity – a South African scholar informing her how student activism was the heartbeat of the anti-apartheid movement.

Notes Yousafzai in the prologue, the displaced – of whom she once was aged merely 11 – are human beings with hopes for a better future!

A paperback, We Are Displaced is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson UK and distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Available at leading bookstores countrywide, it retails for R280.